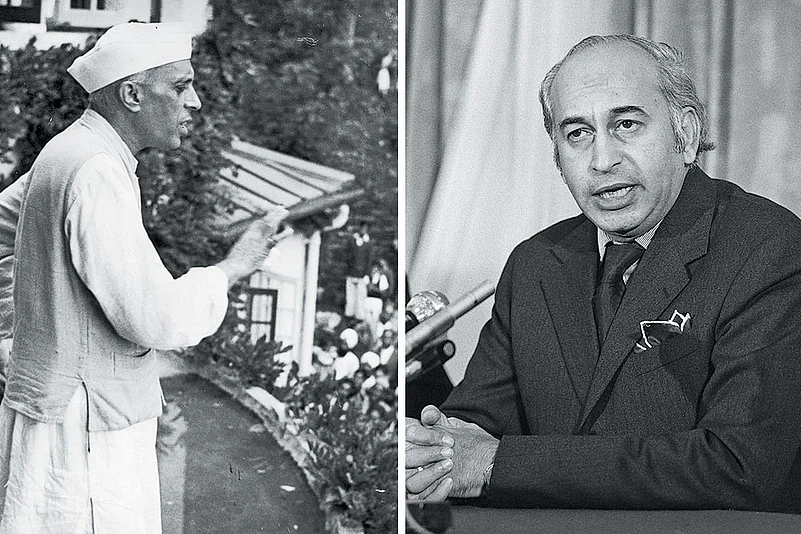

Sixty years ago, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, one of South Asia바카라ôs most brilliantly devilish minds, penned an assessment of Jawaharlal Nehru. Titled 바카라ėIndia after Nehru바카라ô, Bhutto had the document confidentially printed at the State Bank of Pakistan Press, Karachi. Only 500 copies were made. Since Bhutto was a minister at the time in Field Marshal Ayub Khan바카라ôs government and what he had to say about India바카라ôs first prime minister was not quite palatable to the Pakistani establishment, he found himself constrained to withdraw as many copies as could be retrieved. However, the very efficient Indian diplomats in Karachi had managed to secure a copy, and a copy of that copy somehow found its way into the Haksar Papers.

This 60-year-old assessment, made by India바카라ôs most trenchant critic, makes rewarding reading, particularly in the current season of demonising Nehru. Bhutto바카라ôs is a masterly overview of India바카라ôs struggles as an independent nation-state and Nehru바카라ôs role and contribution in imposing a governing order in a land, which for centuries had succumbed to the outsiders바카라ô armies and firmans (orders). Bhutto바카라ôs unsentimentally prescient judgement reads:

바카라ú...The myth and image of Nehru were greater than the man. Although he committed aggression, alienated his neighbours, suppressed his opponents, made mock convenience of his ethics, he was Nehru the redeemer of 400 million people, a valiant fighter who led his people to freedom and, for the first time in 600 years, gave them a place in the sun.바카라Ě

Bhutto is extravagant in his praise of Nehru바카라ôs foreign policy in the first ten years. Because Nehru had the intellectual bandwidth and 바카라úsufficient knowledge of history to visualize the mellowing influence of evolutionary forces,바카라Ě he did not fall for the Washington-centric ideological confrontation with the USSR and its Communism. Writes Bhutto (remember this is in 1964): 바카라úMore than a decade ago, Mr. Nehru observed that 바카라ėCommunism has become outdated.바카라ô This observation was made at the height of Communism바카라ôs monolithic unity and revolutionary drive.바카라Ě The man who one day would be the leader of Pakistan had the grace and the self-assurance to note: 바카라úHe became the statesman and the sage who had to be heard and whose advice had to be measured by rival forces.바카라Ě No music this to the legions of Nehru-haters strutting on the national stage today!

Admittedly, Bhutto is equally scathing in assessing Nehru바카라ôs foreign policy in the second half of his prime ministerial innings. Bhutto is predictably uncharitable to Nehru vis-√†-vis Pakistan: 바카라úNehru바카라ôs main theme was to preach hatred against Pakistan. He was the new State바카라ôs bitterest opponent. He made it his life바카라ôs mission to isolate Pakistan and to create difficulties for Pakistan.바카라Ě Right or wrong, this 60-year-old Pakistani judgement takes the fizz out of our current rulers바카라ô ultra-nationalist assertion of an unprecedented hostility to Pakistan.

It is understandable that any intelligent Pakistani should have envied India for its constitutional governance and stability바카라Ēa blessing that eluded Jinnah바카라ôs nation-state. And, no one can deny that Bhutto was an extremely intelligent man. Educated as he was at Oxford and sufficiently schooled in Pakistan바카라ôs already crooked power-sharing arrangements, Bhutto could make a nuanced appreciation of Nehru바카라ôs statecraft. He is particularly laudatory in how Nehru tamed the bureaucracy, which had long believed that 바카라úthe British Raj was held by their prowess and intellect.바카라Ě Nehru would have none of the ICS-wallahs바카라ô pretensions. No political role for the Civil Services. 바카라úNehru exercised such a Caesarean control over these prefects of civil authority that they soon changed their traditions and mentality바카라Ě and eventually became a responsible and legal instrument of constitutional authority and political stability.

At the same time, Bhutto is unable to appreciate another crucial element in Nehru바카라ôs statecraft: the civil-army relationship. 바카라úWith all Nehru바카라ôs unrivalled qualities and wisdom, he hopelessly misjudged the role of armed forces.바카라Ě By the time Bhutto was making this judgement he had probably internalised the Pakistani army바카라ôs self-proclaimed mission as 바카라úguardians of the state바카라Ě. Obviously, Bhutto could not factor in that Nehru was a product of a mass freedom struggle that had unseated a mighty colonial power and therefore, was not in awe of institutions of coercion and violence. No Pakistani leader ever had that elemental assurance that comes from commanding the respect and allegiance of the masses, and, therefore, all of them, before and after Bhutto, limply conceded to the armed forces a veto power in Pakistan바카라ôs internal and external affairs. This remains Pakistan바카라ôs un-exorcised curse till this day; but, curiously enough, Bhutto바카라ôs indictment of Nehru on this count has been kneaded into our own 바카라únationalist바카라Ě narrative over the last few years.

The bottom-line of Bhutto바카라ôs evaluation was that after Nehru, India was no longer a stable arrangement and that it was bound to break up. The last para of this unique document reads: 바카라úNehru바카라ôs magic touch is gone. His spell-binding influence over the masses has disappeared. The key to India바카라ôs lasting unity and greatness has not been handed over to any single individual. It has been burnt away with him.바카라Ě

Probably, Bhutto was reflecting the Ayub Khan regime바카라ôs collective view of post-Nehru India: a weak country under a weak prime minister. Perhaps it was this gross misreading that goaded the old Field Marshal to instigate the 1965 war against India, thinking that the 바카라úpocket-size바카라Ě Shastri would not be able to stand up to the tall Pathan. The entire Pakistani establishment would have watched with glee how the southern states had gone up in flames over the Hindi issue in the early two months of 1965; the generals and their civilian henchmen like Bhutto must have thought it was the perfect time to give one more 바카라údhakka바카라Ě (push) to India and the whole edifice Nehru built would collapse.

What the ruling Pakistani clique had not bargained for was the brilliance of Indian soldiers like Lt General Harbaksh Singh and Air Marshal Arjan Singh and the professional calibre and courage of the Indian armed forces. By its outstanding performance, the Indian military brass debunked, once for all, Bhutto바카라ôs indictment of Nehru바카라ôs policy of keeping the armed forces away from the politicians바카라ô quarrels. And certainly, Field Marshal Ayub Khan and his cronies could not understand the strength and depth of legitimacy that accrued to the Indian political leadership from democratic mandates.

Nonetheless, Bhutto in this 1964 assessment was insightful enough to remark on Nehru바카라ôs preference for 바카라úthe road of compromise and argument바카라Ě in holding and consolidating 바카라úthe greatest of all contradictions called India.바카라Ě Bhutto and his master, the Field Marshal, forgot to apply this simple lesson of statecraft in their own country and eventually paid the price of a civil war, leading to an independent Bangladesh.

Our current crop of leaders may not have any use of the Nehruvian legacy but the principle of 바카라úcompromise and argument바카라Ě remains the only workable formula for all rulers in South Asia.

(Views expressed are personal)

Harish Khare is a Delhi-based senior journalist and public commentator