바카라úPehle Payal ko pata, fir hata sawan ki ghata,바카라Ě (Woo Payal first and then dump her when you are done) Rocky advises a barely post-pubescent Rajiv in Ishq Vishk (2003) when he has an ardent dilemma: he does not have someone to hook up with on his freshman college trip. Amrita Rao바카라ôs Payal Mehra is straight-up out of the Sooraj Barjatya universe: she is simple, she is sanskaari, and Shahid Kapoor바카라ôs Rajiv knows that all too well. But the ghost of Kabir Singh바카라ôs (2019) past lurking in Rajiv바카라ôs psyche convinces him to manipulate Payal nonetheless.

In Ishq Vishk, Rajiv바카라ôs bildungsroman arc is disturbingly shaped through both emotional and physical violence upon Payal바카라ôs body, mind and soul. When he tries to force himself on her, she rejects him. And Rajiv promptly takes a leaf out of the incel textbook and insults Payal. He calls her a 바카라úbehenji바카라Ě who should have felt honoured to be desired by him. However, long before Rajiv learnt to crawl through the toxic sewers of deranged masculinity, Bollywood had already laid the groundwork for normalising such behaviour in the guise of romance.

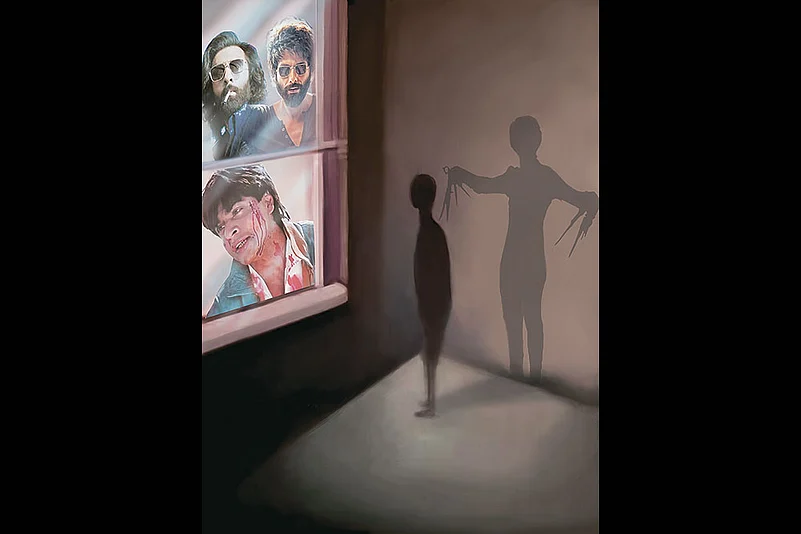

One of Shah Rukh Khan바카라ôs most problematic Rahuls (an achievement of sorts) crooned, 바카라úTu haan kar ya na kar, tu hai meri Kiran,바카라Ě (Whether you say yes or no, you are mine Kiran) in the 1993 film Darr and sent shivers down an unsettled Kiran바카라ôs (Juhi Chawla) spine. The psychological thriller hit the nail on the head about how obsession, stalking, harassment, and a man바카라ôs inability to take rejection is not at all romantic but downright terrifying. But after the massive success of Darr, the audiences sympathised more with Rahul, not the hero who saved the heroine바카라Ēa fact that Sunny Deol was not too happy about.

Movies like Darr, Baazigar (1993), Anjaam (1994) were game-changers in 1990s Bollywood, when courtship had already become synonymous with coercion. From Aradhana (1969) and Sholay (1975) to Dil (1990) and Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge (1995), the message had been consistent: if a man just tries hard enough, the woman will be impressed. Her initial rejection isn바카라ôt her final word; it바카라ôs a negotiation. 바카라úHaseena maan jayegi바카라Ě (literally, 바카라úthe beauty will eventually say yes바카라Ě) has not been a subplot but the very foundation of nearly every mainstream romantic film for decades. This has been the bedrock of David Dhawan바카라ôs entire filmography. From Aamir Khan to Akshay Kumar, they have all been guilty of perpetrating this trope.

In such a scenario, where the ideas of basic consent are deemed redundant, conversations about enthusiastic consent바카라Ēexplored in Pink (2016)바카라Ēhave no space. This is why many viewers struggle to recognise films like The Great Indian Kitchen (2021) or its remake Mrs. (2024) as portrayals of marital rape, brushing them off as mere depictions of 바카라ėbad sex바카라ô. It바카라ôs also why they fail to connect the dots between on-screen entitlement and real-life violence바카라Ēthe one depicted in Chhapaak (2020), where Deepika Padukone바카라ôs Malti becomes an acid-attack survivor. Malti바카라ôs story, based on Laxmi Agarwal, reflects a brutal truth: Laxmi was a minor, just 15, when a 32-year-old man, Naeem Khan, threw acid on her face for rejecting his advances바카라Ēa horrific consequence of male entitlement to women바카라ôs bodies.

The Incel Culture

Adolescence (2025) has sparked a much-needed debate about incel culture and manosphere across the globe. Even in India, everyone from media outlets to millennial parents are raising concerns about helping young men navigate a life where incel influencers like Jordan Peterson and Andrew Tate are more easily accessible than ever before. The likes of Carry Minati, Ranveer Allahbadia, Elvish Yadav and Samay Raina have taken up the mantle closer home to condition young men in the language of toxic masculinity. It바카라ôs impossible to ignore how these ideologies are shaping young minds today.

Adolescence dives into the life of a young boy, Jamie Miller, who gets pulled into the toxic orbit of online bullying. The show excavates how his anger from feeling rejected ultimately leads to the loss of a life. Much of the story is rooted in the rhetoric of modern-day incels. This show is unflinching in its portrayal of how young men are socialised to feel entitled to women바카라ôs attention and affection, and yet, what바카라ôs ironic is that Adolescence isn바카라ôt exactly breaking new ground. These ideas were seeded much earlier, especially in India and, by extension, its populist cinema. Long before the terms 바카라úincel바카라Ě and 바카라úmanosphere바카라Ě were even part of the cultural lexicon. When Aman said: 바카라úChhe din, ladki in바카라Ě (Six days and the girl will give in) in Kal Ho Naa Ho (2003), it wasn바카라ôt a joke, it was the playbook.

Blueprint for Manosphere

Bollywood has been selling the idea that a woman바카라ôs 바카라úno바카라Ě is just a challenge for the hero to overcome for nearly a century now. Some of it is a reflection of patriarchal sentiments while some of it actively goes on to shape it. And all is deemed good because the hero gets the girl at the end anyway. From the golden age of Hindi cinema to the era of pan-Indian blockbusters, Indian films have consistently romanticised the disturbing idea: 바카라úUske na mein bhi haan hai바카라Ě (There바카라ôs a yes even in her no).

From obsessive lovers rebranded as romantic heroes to stalking framed as sincerity, our cinema has normalised entitlement.

In Bollywood, the trope took root early. Films like Junglee (1961) and Aradhana (1969) showcased the romantic hero as a gentle stalker, wooing women who initially resist. But the trope solidified in the 1970s and 80s, with larger-than-life male leads who treated rejection as foreplay. Sholay (1975) offered a comedic spin with Dharmendra바카라ôs relentless pursuit of Basanti. In Amar Akbar Anthony (1977), each male protagonist wins over women through a combination of persistence, slapstick, and dominance. The 90s sealed the trope with Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge (1995), where Raj바카라ôs repeated boundary-pushing is framed as charming, and Simran바카라ôs eventual surrender is presented as inevitable.

When I was in high school, sites like Reddit and 4chan바카라Ēthe digital watering holes for incel rage바카라Ēwere not yet popular in India. Yet, that sickening incel mentality was already deeply rooted in our psyches. I was chastised by another girl for saying no to her friend despite him asking me out multiple times. Him stalking me and sitting outside my classroom should have charmed me, she had said. 바카라úWho did I think I was?바카라Ě she had asked. When my best friend was pursued by another guy for years, despite her repeated rejections, everyone else바카라Ēour friends and peers바카라Ēbelieved she would give in eventually. It was inevitable, they proclaimed. 바카라úShe simply didn바카라ôt yet know she wanted it too.바카라Ě

This is the coda Bollywood has been promoting as romance for decades. It바카라ôs a pattern that mirrors the entitlement seen in today바카라ôs incel culture. This framework has become so entrenched that it often transcends genre. In action films, romantic subplots still relied on coercive flirtation (Dabangg (2012), Rowdy Rathore (2012)), while even supposed 바카라úrom-coms바카라Ě used manipulation as the love language (Humpty Sharma Ki Dulhania (2014), Badrinath Ki Dulhania (2017)). At its worst, the trope enables outright harassment. At its best, it dictates that women should do the emotional heavy lifting and teach their men about equality and respect. However, the bottom line remains that 바카라útrue love바카라Ě involves stalking, emotional blackmail, and even physical aggression바카라Ēbecause the man knows better than the woman what she really wants.

This toxic narrative isn바카라ôt confined to Bollywood alone. Even South Indian cinema isn바카라ôt immune. Take Baahubali: The Beginning (2015), where the hero, Shivudu (Prabhas), through sheer force of will, strips away Avantika바카라ôs armour both literally and metaphorically. He 바카라úconquers바카라Ě her, not by respecting her autonomy, but by taming her. The existence of this gaze is also ironic in a story where Shivudu바카라ôs father Amarendra Baahubali caused an entire civil war after chopping off the head of the man who threatened to touch his wife Devasena inappropriately. Baahubali serves as a compelling case study in how the morality of actions is often determined by the identity of the one performing them.

The lines between romance and harassment are blurred deliberately. This helps position men as saviours when they are the perpetrators themselves. The hero and the villain get to fight over a woman바카라ôs body as if it바카라ôs their territory to claim. With consent often subordinated to the hero바카라ôs status, rather than the nature of his actions, our fiction keeps repeating that if he바카라ôs the lead, he바카라ôs entitled; if you바카라ôre the object of his desire you have no choice. From Tere Naam (2003) to Arjun Reddy (2017) and its Hindi remake Kabir Singh, mainstream cinema in India and its majoritarian audience does not want to even pretend about respecting women or their autonomy.

When a film like Thappad (2020) comes along, it becomes an outlier. It becomes part of a movement that has been trying to push back. Films like Queen (2013) and Piku (2015) create a separate space where female protagonists do not need to be won over by persistence. They get to prioritise self-worth and boundaries. And stories like The Lunchbox (2013) get to depict love as a space of emotional honesty.

The internet may have given incels a louder microphone, but Bollywood handed them the script decades ago. From obsessive lovers rebranded as romantic heroes to stalking framed as sincerity, our cinema has normalised entitlement and celebrated male desire as destiny. The rise of incel culture in India is simply the inevitable evolution of a mindset that has always existed in a patriarchal system. Until our stories start valuing consent as clearly as they glorify conquest, we바카라ôll keep raising generations that confuse love with control바카라Ēand call it romance.

Debiparna Chakraborty is a film, TV, and culture critic dissecting media at the intersection of gender, politics, and power

This article is part of Outlook바카라ôs April 21, 2025 issue 'Adolescence' which looks at the forces shaping teenage boys today바카라Ēonline misogyny, incel forums, bullying, and the chaos of the manosphere. It appeared in print as 'Haseena Man Jaayegi'.