If you have read Salman Rushdie, you will know that he바카라ôs forever nostalgic about Bombay, his childhood fairyland whose magical dust has fuelled some of his finest novels, most famously Midnight바카라ôs Chil¬≠dren. He lovingly calls his former home 바카라úmy lost city바카라Ě. In Maximum City, Suketu Me¬≠h¬≠¬≠¬≠ta writes, 바카라úEach Bombayite inhabits his own Bombay.바카라Ě And long before these modern-day bar¬≠¬≠ds there was Saadat Hasan Manto, whom aut¬≠hor Aatish Taseer has described as the quin¬≠¬≠t¬≠essential 바카라úBombay writer바카라Ě. Literature, as we can see, has always had a great love affair with Bom¬≠bay. But the city is also home to Bollywood, which has tried to capture its throbbing pulse and never-say-die spirit in its own way. According to Hin¬≠di cinema, the maximum dreams of the maxi¬≠¬≠mum city are often matched by the maximum nightmares.

I am a Mumbaikar myself, and to be one is to navigate two opposite worlds at the same time. One is that of the poetic fantasy바카라Ēor the 바카라úbeautiful forevers바카라Ě, as writer Katherine Boo puts it바카라Ēwhereby we try to romanticise its 바카라ėCity of Dre¬≠¬≠ams바카라ô aspect that reflects endless ambition, enterprise and Bambai se aaya mera dost swag. The other is its more realistic manifestation, a megacity of hard-knock existence where dreams come to die. (Watch Gharaonda, a 1977 tale of typical Bombay struggle in which lyricist Gulzar reserves his most plaintive verses that define a more realistic side of the Mumbai experience). Here, people lead 바카라úlives of quiet desperation바카라Ě, to borrow from Henry David Thoreau. This dichotomy has been a recurring motif in many Hindi films, particularly those that have attempted to celebrate Bombay/Mumbai as a character rather than using it just as a fanciful backdrop.

But then, every movie set in Mumbai these days claims to show the city as a character. Only one as rare as the Dev Anand starrer Taxi Driver (1954) has the gumption to make that assertion explicit by cheekily slipping in 바카라ėcity of Bombay바카라ô in its opening credits alongside other 바카라ėguest artists바카라ô. Like many Dev Anand films, Taxi Driver is as much an ode to the idea of romance as it is a love letter to Bombay. The most unusual thing about the evergreen Anand films is that they depicted Bombay as a lair of crime and shallow glamour. Though inspired by Hollywood noirs, they sweep you into the world of urban underbelly with distinctly Indian twists. With their moral ambiguities and focus on rapidly changing social and cultural mores, they portray a city at the cusp of modernity. In them, the post-Independence opt¬≠imism is very much in the air but often, the protagonists find themselves greatly torn apart by the corrupting influence of the metropolis. Ana¬≠nd바카라ôs other iconic hits of the era like Baazi, CID 바카라Ēbest known for the city바카라ôs de facto anthem Yeh hai Bom¬≠bay meri jaan바카라Ēand Kala Bazar are perfect examples of what you might call the 바카라ėBombay films바카라ô. For old souls, there바카라ôs an unmistakable joy in seeing the then-Bombay at its charming best in these golden-era classics. So much has cha¬≠nged about the city바카라ôs character since and yet, much else remains the same. For example, one of the pleasures of watching the Taxi Driver song Jaayein toh jaayein kahan on YouTube is not just to hear a young Lata Mangeshkar바카라ôs nasal pitch but also to see an almost pristine Worli sea face where the only time you spot a crowd is when a throng of onlookers gathers behind, perhaps to catch a glimpse of Dev Ana¬≠nd. Today, the Worli sea face neighbourhood is a different beast altogether, though some of the old bungalows are still standing, biding their time as the last surviving link to its idyllic past.

If Dev Anand바카라ôs Bombay was a den of gambling, vices and vamps, his contemporary, the inimitable Raj Kapoor바카라ôs Bombay was worse바카라Ēcold-hearted and indifferent. The Bombay of Shree 420 (1955) is all maya (as exemplified by the character of Nadira) and Kapoor바카라ôs innocent fool quickly gets sucked into a whirlpool of riches and glamour. The beggar, who meets him at the film바카라ôs opening, puts it bluntly when he says, 바카라úYeh Bambai hai mere bhai, Bambai바카라¶yahan buildingein banti hain cement ki aur insanon ke dil patthar ke.바카라Ě

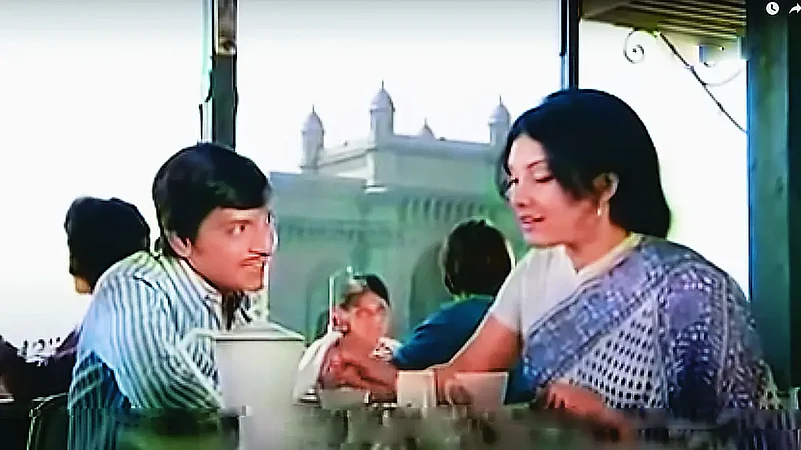

Bombay has been a muse to filmmakers from the 1970s and 바카라ô80s, too. The city has been immortalised in mainstream (here바카라ôs looking at you, Manmohan Desai and Prakash Mehra), middle and parallel cinema alike, but not always in a tone that suggests celebratory or larger-than-life. Take Basu Chatterjee바카라ôs films. Khatta Meetha and Baton Baton Mein are predominantly set in Bombay wh¬≠i¬≠le Rajnigandha includes the lovely song Kaeen baar yunhi dekha hai shot in a cab as it meanders through Bombay바카라ôs streets. But it is in his endearing Chhoti Si Baat, starring Amol Palekar and Vidya Sinha, that Chatterjee successfully encapsulates an unhurried middle-class romance blossoming between two pure souls in a city that notoriously never sleeps. The now-defunct Samovar cafe and Jehangir Art Gallery at Kala Ghoda, Gateway of India and bus stops advertising the latest hits from the dream factory...Chhoti Si Baat바카라ôs Bombay is as quaint as it can get.

Unlike Basu Chatterjee, the Bombay found in his parallel cinema counterparts like Govind Nihalani, Muzaffar Ali and Saeed Akhtar Mirza바카라ôs cinema are more angst-ridden. Particularly Mir¬≠za바카라ôs Salim Langde Pe Mat Ro (1989) and Albert Pinto Ko Gussa Kyun Aata Hai (1980) portray the aspirations and hardships of the minorities who are being left behind as the financial capital of India gets richer and yet, simultaneously more ins¬≠ular. But it is Naseem (1995) that by far rem¬≠ains Mirza바카라ôs most personal film. It tells the story of a grandfather (played by the legendary Urdu poet Kaifi Azmi) and his granddaughter in the days leading up to the Babri mo¬≠sque demolition. In a 2012 interview, Mirza told this writer, 바카라úNas¬≠eem was the epitaph for me바카라Ēepi¬≠taph to an age, to a time, and perhaps, also to cinema.바카라Ě

Mirza may have never made another worthwhile film after Naseem but his work seems to have influenced a generation of filmmakers. From Mira Nair바카라ôs searing Salaam Bombay! (1988) to Zoya Akhtar바카라ôs Gully Boy (2019), Mir¬≠za바카라ôs rooted, neorealist style has made him a uni¬≠que voice of subaltern Mumbai. A landmark of its genre, Salaam Bom¬≠bay! is a stark depiction of the under-city, hitting you with its haunting raw power and the epoch- making Ganesh Chaturthi climax that became a template for nearly every Bombay film in the decades to follow바카라ĒSatya and Vaastav to name just two. Journalist Uday Bhatia, who has written Bullets Over Bombay, a terrific book on Ram Gopal Varma바카라ôs Satya, recently told a news portal, 바카라úEveryone thinks of Satya as a gangster film but it바카라ôs actually a film about living in Bom¬≠bay.바카라Ě Movies on Mumbai바카라ôs mafia tend to glamourise crime, making guys like Manoj Baj¬≠payee바카라ôs Bhiku Mhatre or Sanjay Dutt바카라ôs Raghu seem like messiahs.

Instead, pay attention to the sobering wisdom of older underworld figures like Abbaji (Pankaj Kap¬≠ur) in Maqbool. A desi Godfather, Abbaji recites one of the most memorable dialogues about the city in the Shakes¬≠pe¬≠arean tragedy: 바카라úMumbai ham¬≠ari mehbooba hai miyan, hum isse chhod kar Kara¬≠chi ya Dubai nahin jaa sakte.바카라Ě The other unforgettable line goes to the original Bombay chro¬≠nicler. There바카라ôs a scene in Nandita Das바카라ô Manto (2018) in which Manto is leaving for Pakistan after Partition. He바카라ôs accompanied by his friend Shyam in the taxi. As they pass by a favourite haunt, Shy¬≠am offers to settle an old account with the shopke¬≠eper. But Manto (played by Nawazuddin Siddiqui) tells him not to, delivering the punchline of a lifetime, 바카라úMain chahta hoon ki zindagi bhar is sheher ka karzdaar rahoon.바카라Ě

(This appeared in the print edition as "Mumbai Matinee")

(Views expressed are personal)

Shaikh Ayaz is a mumbai-based writer and journalist