In a pivotal scene from The Kerala Story (2023), four female students바카라Ēthree of them crying바카라Ētry to process a traumatic incident: One of them has been molested in a mall. The only composed person among them wears a stern expression and a mauve hijab. 바카라úI바카라ôm sorry guys, but this had to happen,바카라Ě she says. 바카라úDevils need a chance, and you gave them the chance. Thank Allah that he saved you. But did you ever think why, of all the women in the market, this happened to you?바카라Ě She explains: 바카라úBecause only you three바카라Ě바카라Ētwo Hindus and one Christian바카라Ē바카라úwere not wearing hijab. Allah always protects us바카라Ēhe바카라ôs not like your gods.바카라Ě

Nine months later, the 바카라úbrave storytellers of The Kerala Story바카라Ě released a teaser, Bastar. A cop바카라Ēsitting in her office, wearing a bandana바카라Ēcompares the Indian soldiers killed by the Pakistani Army (바카라ú8,738바카라Ě) with Naxals (바카라úover 15,000바카라Ě). When they 바카라úmassacred 76 jawans in Bastar바카라Ě, she thunders, a college celebrated those deaths: 바카라úJNU.바카라Ě She stands up. 바카라úJust think about this: a reputed university celebrates the martyrdom of our jawans. Where does such a mindset come from?바카라Ě These Naxals, she adds, are 바카라úconspiring to dismantle India바카라Ě. Their allies? 바카라úThe left-liberals and pseudo intellectuals.바카라Ě She proposes a final solution: shooting the 바카라úvaampanthis바카라Ě (Leftists).

This genre바카라ôs poster boy, The Kashmir Files, alternated between the militants in 1990 and the 바카라ėANU바카라ô students in 2016, drawing implicit and explicit parallels between them. Made on a reported budget of less than Rs 20 crore, both The Kashmir Files and The Kerala Story earned more than Rs 300 crore. Monetary reward, though, is just the first benefit. Second, recognition, via National Awards (The Kashmir Files won the Best Feature Film on National Integration). Third, power (its director, Vivek Agnihotri, who got Y category security detail after the movie바카라ôs release, is also a censor board member). Other rewards range from special permissions to politicians바카라ô endorsements to tax cuts. Riding the wave of jingoistic films, Kangana Ranaut has transitioned to politics, representing the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) in the 2024 Lok Sabha elections.

If the months before the 2019 elections saw a spate of films demonising the BJP바카라ôs villains (The Accidental Prime Minister, Uri, The Tashkent Files), then this year is no different: Article 370, Bastar, JNU: Jahangir National University. 바카라úIs JNU a haven for anti-nationals?바카라Ě Its trailer asks. Followed by the college students shouting, 바카라úBharat, tere tukde tukde honge [India, you바카라ôll be broken into pieces].바카라Ě Backed by Zee Studios, JNU reproduces the contentious line attributed to Kanhaiya Kumar leading to his arrest바카라Ēlater debunked as doctored바카라Ēmade popular, via countless reruns on TV, by channels such as Zee News. Amid scenes of students바카라ô violence바카라Ēintercut by 바카라úCan one university break the country?바카라Ě바카라Ēthe trailer throws this line: 바카라úIt바카라ôs easier to get a visa for Pakistan, not JNU.바카라Ě

Pakistan. Of course. Often featured as a convenient punching bag in Hindi films바카라Ēalso doubling up as a fount for Islamophobia바카라Ēit has found several companions in recent years, as Bollywood filmmakers have sought villains justifying their Hindu heroes. So the Islamic rulers emerged, then the Congress, then Americans, then, at last, a villain not seen in Hindi cinema before: regular Indians intent on tearing the country from inside바카라Ēthe liberals, the leftists, the intellectuals바카라Ēso much so that they바카라ôre called 바카라úterrorists바카라Ě. Post-2014, Bollywood propaganda resembles a boomerang: It바카라ôs travelled the world to reach home.

In May 2014, when the BJP came to power, propaganda cinema was 102 years old바카라ĒIndian cinema, 101. Its first fictional, feature-length example was IndependenŇ£a Rom√Ęnie (1912), based on the 1877 Romanian War of Independence. Soon, World War I바카라Ēthe first conflict in the age of movie cameras바카라Ēaltered this genre forever. In 1916, the British Empire and the French Third Republic fought the German Empire in the months-long Battle of the Somme. They all made (propaganda) films on it. The British movie showed 바카라úremarkable ideological constraint바카라Ě, wrote Nicholas Reeves in The Power of Film Propaganda: Myth or Reality (1999), presenting the events in a 바카라úmeasured, unemotional, and almost objective manner바카라Ě. The French piece resorted to propaganda-within-propaganda: a war movie made by a country that excluded its ally. The German film answered its British counterpart by claiming its own victory in the battle.

The United States, too, had produced war propaganda바카라ĒThe Battle Cry of Peace (1915), The Kaiser: The Beast of Berlin (1918), Hearts of the World (1918)바카라Ēbut its most famous exponent, like the above Bollywood films, targeted not the enemy outside but the 바카라ėenemy inside바카라ô. A racist drama glorifying the Ku Klux Klan, The Birth of a Nation (1915) was a moral failure but an artistic triumph, pioneering such techniques as close-ups, fadeouts, flashbacks, night-time photography, elaborate extras, musical score바카라Ēand a White House screening.

The next decade saw a new nation greasing its ambition, the USSR, whose founder, Vladimir Lenin, had realised the true powers of cinema. He found an ally in director Sergei Eisenstein whose masterful use of the Soviet Montage Theory transformed both propaganda and world cinema. He used it to stirring results in Battleship Potemkin (1925) and October (1928), dramas commissioned by the Soviet government championing Russian workers and revolution.

On June 30, 1928, a 30-year-old man watched Potemkin for the second time. 바카라úThis film is fabulous, with splendid mass scenes,바카라Ě he wrote in his diary. 바카라úTechnical and scenic shots have incisive penetrating power. And the striking slogans are so cleverly formulated that no one can object. That바카라ôs what makes it dangerous. I wish we had one like that.바카라Ě He was Joseph Goebbels, the Nazi party바카라ôs chief propagandist. Much to his satisfaction, Nazi cinema produced a rousing movie with 바카라úsplendid mass scenes바카라Ě, Triumph of the Will (1935). A 바카라údocumentary바카라Ě capturing the 1934 Nuremberg rally바카라Ēthough Leni Riefenstahl staged several scenes바카라Ēit used wide frames, aerial shots, and deep focus, producing a majestic, arresting effect. 바카라úRiefenstahl was clearly very familiar with Eisenstein바카라ôs films,바카라Ě wrote Alan Sennett in 바카라ėFilm Propaganda: Triumph of the Will as a Case Study바카라ô, 바카라úand used rhythmic montage techniques as well as drawing from Potemkin directly.바카라Ě The Soviets and the Nazis: divided by ideology, united by cinema.

A few years later, World War II re-energised the genre again. Both the Nazis and the major Allied powers바카라ĒGreat Britain, the United States, and the Soviet Union바카라Ēturned to cinema to mould public opinion, solicit support, and demonise opponents. In 1940, the British government established a propaganda wing, the Film Advisory Board (FAB), in India바카라Ēa country experiencing its own nationalist churn. The Indian movie press lambasted its head, Alexander Shaw. (바카라úAn unknown man,바카라Ě said the Filmindia magazine, 바카라úeven in England.바카라Ě) Shaw resigned in 10 months바카라Ē바카라úpartly because he was not accepted by the Indian industry,바카라Ě according to film historian B D Garga바카라Ēand FAB folded soon.

Another propaganda unit replaced it in 1943, Information Films of India (IFI), which made documentaries on, besides the war, the country바카라ôs history, communities, and cultures. Five years later, the Indian government created the Films Division (FD), retaining IFI바카라ôs employees, aims, and mechanics. Like IFI, FD ordered theatre owners to screen its documentaries (making them pay the rent), provided little independence to directors, and produced films marked by omniscient voiceovers (a 바카라ėvoice of god바카라ô style). The Indian government knew what its colonial masters did: that in a country wrecked by a low literacy rate (16% in 1947), cinema was their most reliable바카라Ēand formidable바카라Ēally.

A state-controlled organisation with a long history can바카라ôt be homogenous, as it changes with times and regimes. But its Nehruvian phase stands out for an obsessive and unified emphasis on nation building, where many movies used cunning methods and elisions to parrot the governmental agenda, exemplifying 바카라ėbenign propaganda바카라ô. Such documentaries, many available on YouTube, had varied modes of communication. Their construction of an ideal citizen underscored the importance of selfless individuals aiding the government바카라ôs plans. Good Citizen (1959) for example, set in a village, issued a series of instructions: pay tax, cast vote, get vaccinated. Citizens and Citizens (1962) preached what not to do; Say it with a Smile (1960) taught generosity; The Vital Force (1963) urged people to volunteer for a common cause.

Centred on regular Indians, these films barely featured their voices. Instead, the audiences heard the moralising voice of the state. 바카라úThe viewers weren바카라ôt invited to define development in postcolonial India,바카라Ě wrote Peter Sutoris in Visions of Development (2016). 바카라úIt was the 바카라ėexperts바카라ô who determined the shape of modernity and future directions of the country.바카라Ě Much like colonial documentaries, Tools for the Job (1943) and Community Manners (1943), FD movies drew a clear through line between conscientious citizens and national progress.

They turned theatres into classrooms and the state into a teacher. And like an unwavering disciplinarian, it warned and punished. Consider The Case of Mr Critic (1954), which lampoons a common man sceptical of the government. The movie not just takes constant digs at him바카라Ēby turning him into a ludicrous caricature바카라Ēbut also props him up as a cautionary tale (Mr Critic바카라ôs constant 바카라úpooh-poohing바카라Ě gets him fired) and a symbol of hope (he uses the same government scheme, which he had earlier rubbished, to find employment).

Like IFI, FD made films on Adivasis. Here바카라ôs how New Lands for Old (1952) described them: 바카라úThe land-hungry invaders spared no thought for tomorrow and hack[ed] high-land forests. In their greed and ignorance, they squandered nature바카라ôs resources.바카라Ě Several FD films on Adivasis 바카라úperpetuated colonial-era criticisms of their ways of life,바카라Ě added Sutoris, 바카라úconstruing them as second-class to the modern middle-class lifestyle enjoyed by the filmmakers and [their target audience], urban cinema-goers.바카라Ě

If the state could scold, then only could it soothe바카라Ēlike a headstrong father taming a truant. The Adivasis of Madhya Pradesh (1948), the FD catalogue stated, showed how the 바카라úgovernment-sponsored cooperatives바카라Ě made 바카라úold, orthodox바카라Ě lifestyles 바카라úmodern바카라Ě and 바카라úbetter바카라Ě. And if the FD documentaries didn바카라ôt rebuke바카라Ēor reform바카라Ēthe Adivasis, then it exoticised them. Both Our Original Inhabitants (1953) and Gaddis (1970) called their costumes and dances 바카라úpicturesque바카라Ě. These films, too, seemed to have no interest in, wrote Sutoris, 바카라úhearing Adivasis바카라ô own perspectives about their desire for change and definition of progress바카라Ě.

FD, on the other hand, trumpeted its own vision of progress, fetishising new muscular symbols, likening them to 바카라útemples of tomorrow바카라Ě: dams, canals, factories. India바카라ôs march to industrial modernity in these movies, stated Sutoris, had a homogenising sweep바카라Ēthat one model of economic planning could benefit all Indian villages. Like many FD films, they posited Indian elites as the sole architects of nation building and vanquished all scepticism about such progress (as seen in The Dreams of Maujiram (1966) and Shadow and Substance (1967), where poor Indian farmers were taught patience and shown development, much like Mr Critic).

These films even deceived audiences. They equated almost all economic prosperity to dams, neglected alternative methods to reach the same goals, and ignored the dams바카라ô human and ecological costs바카라Ēin terms of both material (the displacement of villagers) and psychological (the loss of livelihoods, homes, identities). Some documentaries that addressed those concerns, wrote Sutoris, such as River of Hope (1953), painted an extremely optimistic바카라Ēand unrealistic바카라Ēpicture of rehabilitated villagers. 바카라úThese films show that in the postcolonial development regime, some colonial approaches to filmmaking not only survived Independence but indeed snowballed into cinematic representations of development whose fallaciousness surpassed even that of colonial-era documentaries.바카라Ě

In the early 바카라ô50s, as the Cold War began to boil, propaganda cinema welcomed a new protagonist, the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). Deploying an unusual 바카라ėally바카라ô, George Orwell, it dictated the film adaptations of both Animal Farm (1945) and 1984 (1949) by altering characters, scenes, and conclusions, making them anti-Soviet mouthpieces. A book that warned against 바카라ėthought control바카라ô had now been weaponised to perpetuate it. The Agency then 바카라ėadapted바카라ô Graham Greene바카라ôs bestseller The Quiet American (1955), an anti-war novel that questions America바카라ôs involvement in Vietnam, and made it바카라Ēwhat else but바카라Ēanti-communist. CIA바카라ôs Hollywood agent, Carlton Alsop, ensured that American films beamed racial harmony (countering the Soviet message that America was racist). So, through his contacts with casting directors, wrote Frances Saunders in Cultural Cold War (1999), he regularly planted 바카라úwell-dressed Negroes바카라Ě as extras but in a way that they didn바카라ôt look 바카라útoo conspicuous or deliberate바카라Ě. He also sanitised the climax of Arrowhead (1953), removing all references to the US government바카라ôs terrible treatment of the Apache tribe.

The CIA바카라ôs covert propaganda peaked in the 바카라ô50s and early 바카라ô60s, noted Tricia Jenkins in The CIA in Hollywood (2012), 바카라úbut declined by the end of the decade바카라Ě. And by the early 바카라ô90s, with the dissolution of the USSR and a series of intelligence failures and negative portrayals in Hollywood, it faced a threat to its very existence. So, in 1996, it established an entertainment liaison office in Hollywood and appointed Chase Brandon바카라Ēa veteran Clandestine Service officer바카라Ēas its head. The CIA had a simple message for filmmakers: Want our co-operation in making movies (such as access to facilities, officials, and files)? Then let us approve the script. It had adopted the playbook of the Department of Defense which, providing military weapons and shooting locations at subsidised costs, often shaped바카라Ēand controlled바카라Ēfilms. (The Indian Army, as preoccupied with its image, refused to give the No Objection Certificate to a film in 2022, as it showed the armed forces in 바카라úpoor light바카라Ě.)

Brandon바카라ôs collaboration with Hollywood produced many movies and TV shows, glorifying the CIA, such as In the Company of Spies (1999), The Agency (2001바카라ď2003), 24 (2001-2010). These depictions also functioned as recruitment videos, helping the Agency increase its enrolment (which had seen a sharp dip in the last decade). It also nurtured relationships with film stars, most notably Ben Affleck who, besides playing a CIA analyst in The Sum of All Fears (2002), directed the factually dubious Argo (2012), which won the Best Picture Oscar whose announcement was broadcasted straight from...the White House.

The recent Bollywood propaganda screams even when it whispers. Many films make it clear, right from their trailers, that they바카라ôre 바카라úbased바카라Ě on or 바카라úinspired바카라Ě by 바카라útrue events바카라Ě.

And in 2011, the Agency got its best 바카라ėpropaganda gift바카라ô: Zero Dark Thirty (2012). The CIA gave unprecedented access to the makers바카라Ērevealed a Freedom of Information Act request바카라Ēwhile filmmaker Kathryn Bigelow returned the favour, treating the intelligence officers to expensive dinners. Once, while dining with a female CIA officer, Bigelow gifted her black Tahitian pearls. (She gave the jewellery to the headquarters to get it appraised; it turned out to be fake.) The CIA-Hollywood symbiosis seemed especially disconcerting in this case, as the war drama implied that torture tactics had led to Osama Bin Laden바카라ôs capture.

Sometimes the CIA outdid itself, as The Agency바카라ôs creator, Michael Breckner, found out. Over many 바카라ėinformal chats바카라ô, Brandon pitched several ideas to Breckner who incorporated them in the screenplay. Its pilot, for instance, Breckner told Jenkins, 바카라úwas based on the premise that Bin Laden attacks the West and a war on terrorism invigorates the CIA바카라Ě. (Breckner finished writing that episode in March 2001바카라Ēsix months before 9/11.) Chase suggested other subplots as well: a Hellfire missile fired from a drone on a Pakistani general, an anthrax attack on Americans, and a Russian suitcase bomb stolen from the USSR. 바카라úAll these events,바카라Ě said Breckner, 바카라úhappened shortly before or after these episodes aired.바카라Ě Reflecting on his conversations with Chase, Breckner believed that the CIA was 바카라úattempting to test the waters somehow바카라Ě바카라Ēor 바카라úusing the series to workshop threat scenarios바카라Ě.

The recent Bollywood propaganda, in contrast, screams even when it whispers. Many films make it clear, right from their trailers, that they바카라ôre 바카라úbased바카라Ě on or 바카라úinspired바카라Ě by 바카라útrue events바카라Ě, which have been suppressed for long. These movies, then, become a collaborative exercise바카라Ēbetween the filmmakers and the audiences바카라Ēin fact finding. They further that charade by using archival footage, newspaper clips, shocking stats, infusing journalistic spirit in dramas hostile to facts.

They바카라ôve also polished their style. Uri (2019), Thackeray (2019), Tanhaji (2020), Swatantrya Veer Savarkar (2024), among others, have impressive cinematography, editing, and performances. An early scene in Thackeray uses an ingenious match cut: the judge striking a gavel on the bench cuts to karsevaks hammering the Babri Masjid바카라Ētwo Indias, two verdicts. In Swatantra Veer Savarkar, a young freedom fighter, Madan Lal Dhingra, proclaims 바카라úVande Mataram바카라Ě before a noose. After setting up the premise바카라Ēthat violence is necessary, noble, and patriotic바카라Ēthe next scene shows Mahatma Gandhi saying, 바카라úAhimsa parmo dharma [non-violence is the prime duty].바카라Ě Two independent shots, a clever juxtaposition, and a new meaning: this is Soviet Montage cinema바카라Ēor the Kuleshov Effect바카라Ēserving the Hindu rashtra.

The astounding success of The Kashmir Files and The Kerala Story has told producers that they can risk less and aim high바카라Ēand it바카라ôs this return on investment, along with possible political benefits, that바카라ôs made this genre explode. These movies also don바카라ôt need popular actors because in them the state바카라Ēand its most commanding embodiment, Modi바카라Ēis the real star. Maybe some directors have바카라Ēfinally바카라Ēunderstood that in a powerful (or, well, divisive) film the main star is the storytelling itself. What excellent art-house cinema couldn바카라ôt teach Bollywood, hate-mongering did.

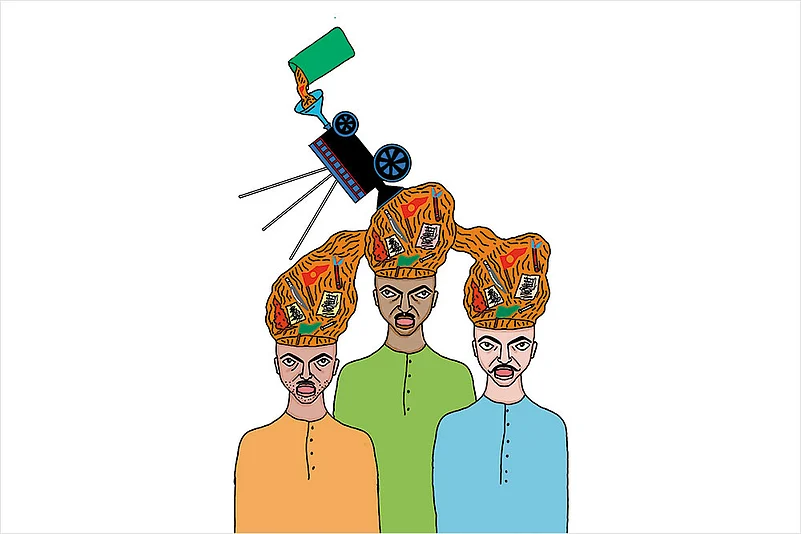

As Bollywood has increased its propaganda production, like Nazi cinema, hunting enemies inside the country, it바카라ôs also manufactured heroes whose prime identities have changed from Indians to Hindus to Hindutvavadis. A biopic on a prominent Hindtuva ideologue, Deendayal Upadhyaya, starring Annu Kapoor, is in the making, while another on the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) founder, K B Hedgewar, will release in 2025, coinciding with the organisation바카라ôs centenary year. Even M K Gandhi hasn바카라ôt been spared. Last year, Gandhi Godse바카라ĒEk Yudh imagined a 바카라ėsober바카라ô conversation between the man and his murderer. A year before, Why I Killed Gandhi, an OTT release, gave inordinate screen time to Godse who called himself secular and a patriot. Another courtroom drama, I Killed Bapu (2023), defended Godse. Hindi cinema바카라ôs current tryst with history and bloodthirst has reached its logical conclusion: for every bit of gandh바카라Ēor dirt바카라Ēin Gandhi, it sees a God in Godse.

(This appeared in the print as 'The Propaganda Files')