Growing up in a small town, I felt an overwhelming sense of wrongness lingering within me, like shadows cast by an unseen presence, even in the absence of explicit terms like 바카라�gay바카라� and 바카라�queer바카라�. These haunting thoughts clung to my mind like ghostly apparitions, weaving their way into every aspect of my being. I was an outsider in a society that didn바카라�t have the vocabulary to explain or accept my identity.

For queer Muslims like myself, this inner conflict can become all-consuming. I was made to feel that my identity was incompatible with my faith and that I had to choose one or the other.

In the halls of the town바카라�s grandest convent school, I stood like a misfit amidst the polished facade, surrounded by an education system that failed to understand me. Their brushstrokes painted a world confined to a binary palette where assumptions of heterosexuality were woven into the very fabric of the institution. I was an out-of-place puzzle piece, struggling to fit into their rigid mould, feeling as if my individuality was shackled. Even the restrooms, labelled with stark signs of 바카라�men바카라� and 바카라�women바카라�, seemed to cast a disapproving gaze, amplifying my discomfort and alienation. Throughout my twelve-year journey, I wandered like a solitary wanderer, engulfed in a sea of alienation, unable to find the words to untangle the tightening grip around my heart and soul.

In a country where queerness exists in shadows, veiled and unspoken, I faced the haunting spectre of rejection from my family and community. My parents, shielded from encounters with openly queer individuals, held tightly to a distorted understanding ingrained with narratives that labelled homosexuality as sinful, a malady forbidden to be uttered aloud. It was a realm where queerness remained hidden, its existence denied, leaving me trapped in a labyrinth of fear.

In my childhood, the absence of characters like me in books and on screen was a glaring void. I never dared to dream that the protagonist of a show could mirror my own identity, as the absence of such role models took a toll on my sense of self. This dearth of representation held a harmful power, silently whispering that my existence was somehow inconsequential, perpetuating the notion that my story didn바카라�t deserve to be told.

Whenever I approached the mosque for daily prayers, I carried an invisible burden of hesitation. Their penetrating gazes felt like daggers, capable of unravelling my guarded truth. A primal fear gripped my heart, envisioning the imam바카라�s condemning voice and the community바카라�s accusatory stares. The thought of my queerness exposed in that sacred space sent shivers down my spine. It was as if my very essence stood bare, twisted and tormented. Paranoia clung to me, a constant reminder of the precariousness of my place, terrified of being cast out, branded as an outsider in a sanctuary that should have embraced me. Why do queer Muslims always have to justify their relationship and connection to God? Isn바카라�t separating people from their creator also a big sin?

Within the sacred month of Ramadan, my faith became a battleground of inner turmoil. The Muslim community surrounding me staunchly reinforced their beliefs, unequivocally deeming queerness as a sin. Each time I dared to broach the subject, my cousin deflected, diverting the conversation or resorting to tasteless humour that only served to deepen the divide. A profound longing consumed me바카라�an insatiable desire to comprehend the roots of such vehement hatred and the scarcity of compassion towards queer individuals. It was a stark reality, witnessing the daily mistreatment of trans people on the streets, their spirits battered by verbal abuse and slurs hurled like sharp stones. The dissonance between the teachings of empathy and the actions of those who perpetuated harm painted a grim tapestry of human hypocrisy.

Many queer Muslims do not hate their religion or God but are coerced into feeling this way by so-called 바카라�religious people바카라� who engage in hypocritical haram policing. At times, I found myself questioning whether it even mattered what I did, as I felt like I was destined for hell anyway. It was then that I realized I needed to find my own way to reconcile my faith and my identity as a queer Muslim by dealing with the shame and guilt that I felt.

My path to Allah hasn바카라�t always been linear. It is filled with twists and turns, highs and lows. One of the most significant challenges I faced was the pressure to unquestioningly accept everything without critical thinking. This came from rigid interpretations of the Quran by scholars which left no space to explore my own interpretations and understandings of the text. I soon realized that I could read the Quran on my own and form my own interpretations, as no one has sole authority over it. Questioning things is not haram in Islam, and I had the power to form my own beliefs and interpretations.

I found comfort in online communities that exist specifically for people like me, spaces that allow people to discuss the complexities of reconciling faith and sexuality or share funny memes and jokes. I found hope and inspiration through The Queer Muslim Project Instagram page, where I came across the stories of remarkable individuals like Gulfraz, a resilient Kashmiri queer Muslim, who breathed life into my weary heart, infusing it with the light of possibility and new-found optimism. And then, there was Haseena, a beacon of courage and resilience, a trans activist hailing from Lahore, whose unwavering authenticity emboldened me to embrace my true self without fear or apology, and many people who affirmed that my relationship with God is personal.

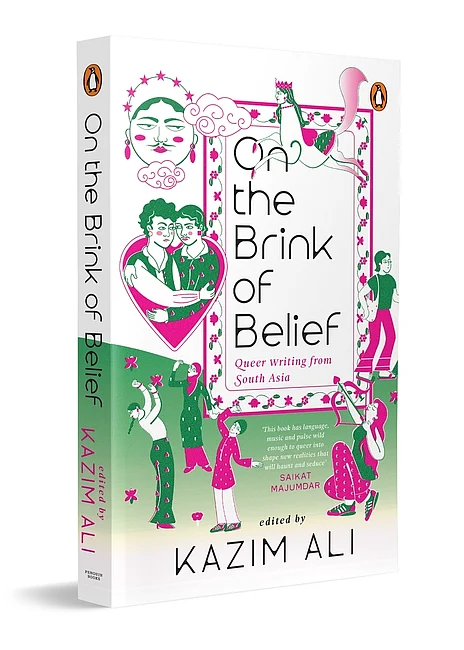

(Excerpted with permission from 바카라�On the Brink of Belief: Queer Writing from South Asia바카라�, edited by Kazim Ali; Penguin Books)