Directed by Zuzana KirchnerovÃĄ, herself a parent to a disabled child, Caravan makes its world premiere at the 78th Cannes Film Festival as a quiet but defiant counterpoint to the slick emotional manipulation we have come to expect from films about disability. From Rain Man (1988) to Forrest Gump (1994) to the upcoming Sitaare Zameen Par (2025), there are plenty of stories out there that centre the exceptionalism of its disabled subjects, often painting them as autistic savants, either to redeem the able-bodied and neurotypical protagonist or to push the cloying idea of 바카라difference as superpower.바카라

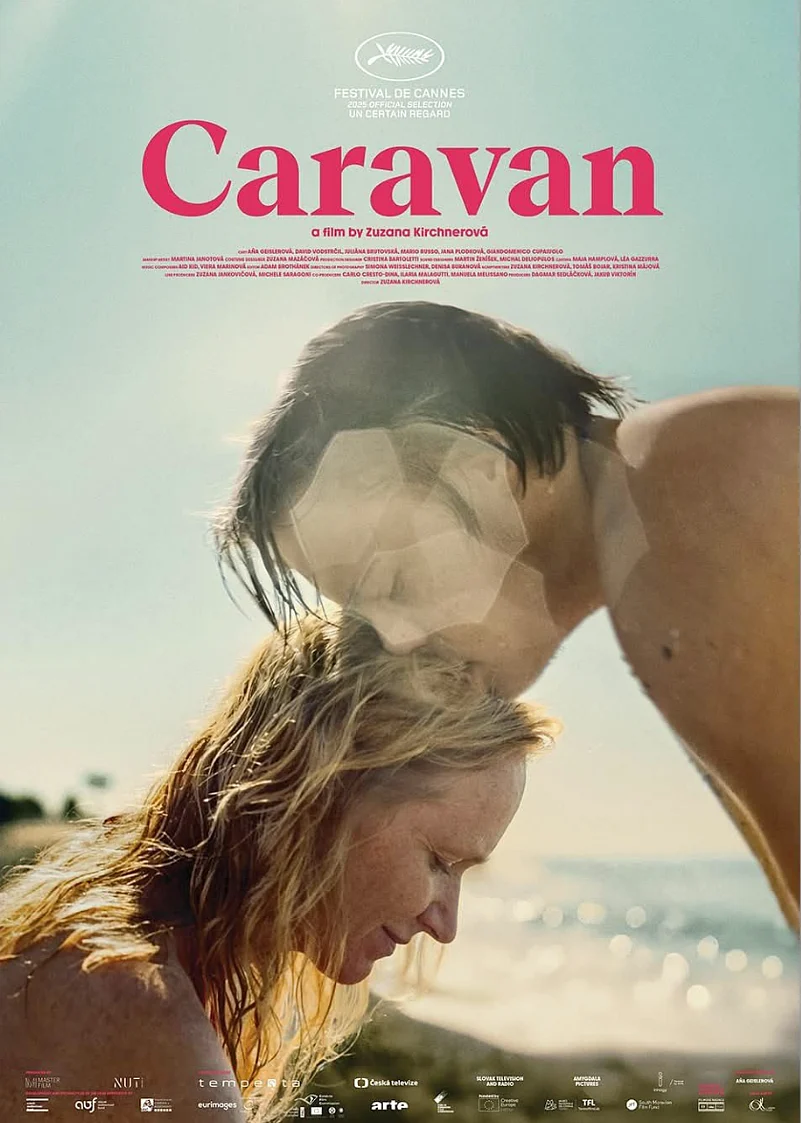

KirchnerovÃĄ, by contrast, strips Caravan of these crutches and, in doing so, reveals something infinitely more honest, and more painful to witness. It바카라s a cinematic cousin to Paromitar Ek Din (2000) in that sense. Caravan is an unflinching debut that expands the cinematic language of disability and motherhood on screen. KirchnerovÃĄ, who won the CinÃĐfondation Prize at Cannes in 2009 for her short BÃĄba, draws from her own life as a mother to a child with Down syndrome and autism to shape Caravan바카라s intimate, lived-in narrative. The film also marks a rare Cannes selection for Czech cinema바카라the first since Jan Å vankmajer바카라s Faust in 1994, and before that there was VÄra ChytilovÃĄ바카라s Fruit of Paradise in 1970.

Caravan dares to look squarely at the bone-deep exhaustion of mothering a child with complex needs without offering tidy resolutions or the usual cinematic contortions of inspiration porn. It neither romanticises nor sensationalises as it follows Ester (Anna GeislerovÃĄ, who is devastating in her restraint), a mother on the brink. Her son David (played by David VostrÄil in a commendable and committed performance) has both Down syndrome and non-verbal autism, and his outbursts are not framed as plot points to be overcome, but as everyday, embodied expressions of his frustration, confusion, and sensory overload.

Caravan opens with Ester gently reassuring her son David that their vacation will go smoothly. It's an intimate moment between mother and son that carries a lot of hope you know will not manifest into reality. This fragile calm unravels soon enough. When David destroys the living room at their shared vacation home, the consequences are not cinematic but realistic and casually cruel. Ester바카라s friends, Tomasso and Petra (Giandomenico Cupaiulo and Jana PlodkovÃĄ) and their two young daughters, pity Ester, pity themselves, and then promptly want them gone. Ester leaves with the old caravan dotted with memories of her carefree days with Tomasso and Petra, long before their children came along.

The film바카라s titular caravan becomes both an escape and a way back home for Ester and David. Fleeing the vacation home and its phoney, bourgeois sympathies, Ester and David set out on a road trip across the Italian countryside. This road trip offers no epiphanies, only intermittent grace in the people they meet along the way. They encounter strangers바카라some generous, some kind, some hostile바카라but KirchnerovÃĄ avoids the usual moral lessons these interactions generally come burdened with in most films of this kind. Instead, each encounter underlines the slow erosion of Ester바카라s patience, dignity, or identity. This one hit close to home. I saw my mother's exhaustion in Ester. I saw my father's frustration in her too. As someone with a high-needs autistic sister, the exhaustion and agony intertwined with the aching love Ester feels for David is all too familiar for me. But so are the tender moments full of glimmer.

The film introduces Zuza (Juliana BrutovskÃĄ-OÄūhovÃĄ), a pink-haired, free spirited wanderer who briefly becomes a lifeline for Ester. Together, they dance at raves, look for odd jobs, scrounge through their last few coins, laugh, play, swim and have fun at the beach. For a moment, it starts to feel like the vacation Ester and David needed and went looking for with their discordant friends.

Zuza바카라s presence in the film is like an exhale after too many held breaths. She offers Ester and David companionship without pity, kindness without judgement, and help without sanctimony. But like all such reprieves in the lives of long-term caregivers, her presence is temporary. Zuza leaves abruptly, leaving behind a note and her phone for David. The abandonment stings, even more so for its predictable ordinariness. In a film so attuned to the rhythms of perseverance, even small acts like this can feel triggering.

KirchnerovÃĄ바카라s direction is visually restrained but emotionally unguarded. The Italian countryside바카라so often aestheticised in cinema바카라is rendered here as slightly indifferent and sometimes even unwelcoming. The film바카라s rhythm also mirrors the daily unpredictability of parenting a high-needs child: quiet, then chaotic, followed by numbness. Instead of cinematic catharsis, KirchnerovÃĄ just depicts the slow, grinding continuation of care through life바카라s ups and downs.

One of the film바카라s quietest but most radical choices is its acknowledgment of David바카라s sexual curiosity as well as Ester바카라s sensuality without any pathologising. In a world that often strips disabled people, as well as mothers, of bodily autonomy and desire, Caravan refuses to show Ester as a perennially self-sacrificing, sexually neutered woman. What cuts through these moments of burning need for Ester is the reality that she cannot commit to creating space for any of it because of David.

The screenplay by KirchnerovÃĄ and TomÃĄÅĄ Bojar resists melodrama. Cinematographers Simona Weisslechner and Denisa BuranovÃĄ, along with editor Adam BrotÃĄnek, lend the film a lyrical austerity. It makes Caravan effective but it is also what will make it difficult for some to sit through it. Even for those of us who have lived on the edges of this reality바카라siblings, partners, parents, or children to those who need more than we can sometimes give바카라Caravan will not be an easy watch.

Caravan refuses to leave you feeling uplifted. Instead, it asks you to sit in the discomfort of witnessing a mother바카라s life becoming smaller, harder, and lonelier. It portrays caregiver burnout as a reality that consumes your entire being. And it understands something few films deign to articulate바카라that even the most ardent love between a caregiver and their dependent is often not enough to save anyone from drowning.

Caravan premiered in Un Certain Regard at Cannes Film Festival, 2025.

Debiparna Chakraborty is a film, TV, and culture critic dissecting media at the intersection of gender, politics, and power.