M.K. Raghavendra is known for trenchant views of cinema he does not appreciate and in the introduction of this almost-fine history of South Indian cinema that he has edited, he does not disappoint. For instance, 바카라�the Kannada films of Upendra바카라�such as A (1997)바카라�often display the raw aggression of toilet graffiti and can make genteel spectators apprehensive about what they could be seeing바카라�. Raghavendra바카라�s chapters on Kannada cinema, under 바카라�A Political History of Kannada Cinema바카라�, are the most fascinating.

After moving on from mythologicals, many films made in the early years of the cinemas of South India dealt with the vagaries of caste, and Kannada cinema was no different. Raghavendra points out the shorthand Kannada cinema used to delineate caste. 바카라�Landowners denoted as gowdas or sowkars may be taken to be Vokkaligas; when people pursue vocations which require education바카라�doctors, teachers바카라�they are usually Brahmins,바카라� writes Raghavendra. He writes about the linguistic reorganisation of states in 1956 and the formation of Karnataka from the erstwhile princely state of Mysore and parts of surrounding states.

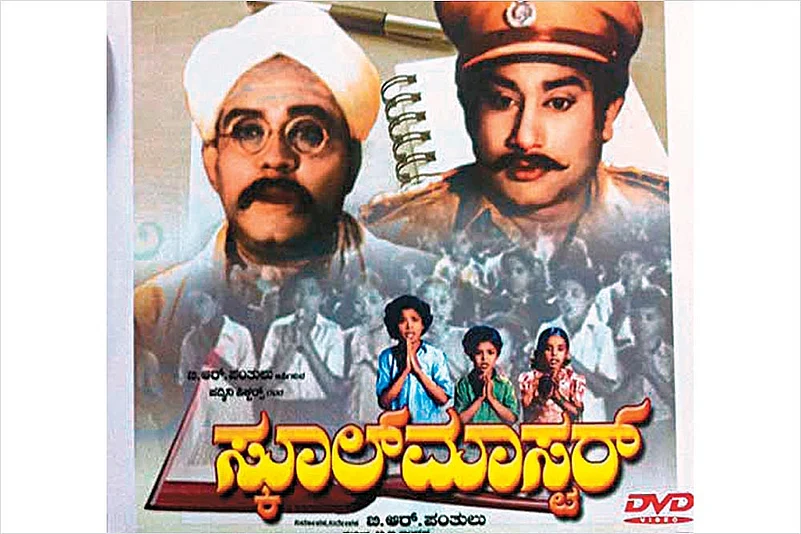

It is here that he presents an absorbing theory바카라�where some films represent Greater Mysore and others all of India. In the case of B.R. Panthulu바카라�s School Master (1958), he postulates that the village in the film refers to Greater Mysore, and the outside to all of India. The titular school master is a local, but has acquired his reformatory skills outside and could be 바카라�an agent of Nehruvian modernity바카라�. He applies this theory to film after film with telling effect. Of course, no history of Kannada cinema is complete without the overarching presence of Rajkumar and Raghavendra explores the late actor바카라�s influence and characters in some depth.

The book begins with N. Kalyan Raman바카라�s chapters on Tamil cinema바카라�바카라�Dream world: Reflections on Cinema and Society in Tamil Country바카라�. After the usual mythological period, Raman looks at how the political scenario in Tamil Nadu over the years, beginning with how the Dravidian movement and its various offshoots had a direct effect on cinema. The effects of caste on Tamil cinema are also explored. In all, for those unfamiliar with Tamil cinema, history, society and politics, Raman바카라�s chapters are almost a perfect primer, a stepping stone to deeper reading, if you will. Almost curiously, Raman chooses to ignore the biggest phenomenon ever in the Tamil film industry바카라�Rajinikanth. Though the star system is present and accounted for and all the important stars are duly name-checked, Rajinikanth is mentioned precisely once. 바카라�The sway of big-budget entertainers starring Rajinikanth and Kamal Haasan took hold of the viewers from the mid-바카라�80s, and the conservatism바카라�both political and social바카라�inherent in mass-market entertainers with a lot of investment at stake pushed all dissent to the margin.바카라� That바카라�s it. Nothing about the reflection of Tamil society and politics in Rajinikanth바카라�s films, nor the actor바카라�s overtly political messages in his later work.

Elavarthi Sathya Prakash바카라�s 바카라�Telugu Cinema: A Concise History바카라� is precisely that. Apart from tackling the social, political and caste themes, as in the other chapters, Sathya Prakash also explores the music of Telugu cinema, a subject not often explored in English writing about the industry. Trivia hounds and quizzers would do well to read these chapters, as they are crammed with information that can be parsed into questions. Like with Rajinikanth in the Tamil chapters, there is a glaring omission바카라�there is no mention of S.S. Rajamouli or Baahubali.

Meena T. Pillai바카라�s 바카라�Bearing Witness: Malayalam Cinema And The Making Of Keralam바카라� is an efficient look at Kerala바카라�s cinema history (with emphasis on gender politics) and the shaping of the state바카라�s cultural and political identity. The writing is so evocative that you바카라�ll find yourself reaching for YouTube to see what exactly Pillai is writing about. The only minor quibble바카라�while writing about J.C. Daniel, the founding father of Malayalam cinema, Pillai omits to mention the existence of Kamal바카라�s Daniel biopic Celluloid (2013).

Returning to Raghavendra, his introduction uses 2012 statistics to illustrate that Tamil and Telugu cinema has relegated Hindi cinema to third place. If he had bothered to look up 2016 statistics (surely the minimum requirement for a book published in 2017), he바카라�d find that of the 1,907 films certified that year, Hindi had 340, Tamil 291 and Telugu 275. If these and such minor niggles, as pointed out above, are addressed in the next edition, this book will be a valuable addition to any South Indian film buff바카라�s library.

(Naman Ramachandran is the author of Rajinikanth: The Definitive Biography)