Monsoons are the life of nature. They might evoke a sweet thought, a texture for the artist, deep-fried pakoda for the olfact¬≠ory senses, kadak chai as a faithful companion and many lives taking birth out of the earth. However, it is also a curse, an undesirable fate. It showers upon hopes and emotions built over months. It makes cattle and pets scream; the children hide to escape the wrath of this unfriendly season. In balance, monsoons are an act of good faith. If it is more, it is a curse; if not, the preceding dry season prays for its arri¬≠val. The monsoon teaches us each year about the madhyam marga that the Buddha prea¬≠c¬≠hed. Do we have a medium that would capture the soul of monsoons? Can anyone justify the amorph¬≠ous nature of the monsoons? Perhaps we have now. When Outlook pitched the idea of an issue on the monsoons, I started thinking about the concept of rains, which was not alw¬≠ays good for me. I reprobated rain because it would dirty our unpaved pathway, while the gutters would flow into our houses with all the disgusting was¬≠te finding its way into the place where we ate and slept. It reminded me of Nag¬≠raj Manj¬≠ule바카라ôs national award-winning short film Paavs¬≠a¬≠cha Nibandh.

The film triggered many memories. So I tho­u­ght Manjule would be a great entry point for the Outlook piece. He is zen in his approach to the craft of storytelling. He likes horizons, clo­uds, the vastness of the sky and the romance of wind with everything in nature.

It opens with trees swinging in the monso¬≠ons, with smoky clouds suspiciously present in the backdrop. We don바카라ôt know their next move. They might shower down and surp¬≠r¬≠ise you, or continue their long, thous¬≠and-mile journey. Prayers of farmers and peasants mediate their stops. When called upon by the dry lands, they promptly visit their kin in an annual retreat.

I decided to sit with Manjule for this one. He tuned in from his home in Pune, and I joined from Bosnia바카라ôs countryside by the river Fojnica. Man¬≠jule and I caught up after three years. Amid internet glitches, and his son Raya seeking his father바카라ôs att¬≠ention, we conducted the interview.

What바카라ôs with the title of Paavsacha Nibandh?

It바카라ôs many things. We were not sure if the translation worked well. Some consider it to be an Essay About Rain. Our translation was An Essay of the Rain. But it is an essay written by the rain. It could be either.

Rain has the ability to do so many things. Did you mean to keep it abstract?

Correct. We write about rain. Poets romanticise rain and talk of greenery and showers. But the rain I experienced was not with fondness. Here, rain has an agency, and we can write about each other, i.e., the rain and humans and vice versa.

The movie is shot amid heavy rains. How did you choose the locations? What preparations did you make?

The film was shot in Pavna and Mulashi of Pune district. Various scenes were captured in villa¬≠ges within a 40 km radius. We had to shoot in the rain, and after much searching, we finalised a few villages. We had to shoot this in seven days when there was continuous downpour. Our crew was of the same size that we use for a feature-length commercial film. Shooting a film about rain is challenging and demanding. Rain is uncontrollable. It can come and stop abru¬≠p¬≠tly. We chose a time known as mhatari cha naks¬≠tra (grandmother바카라ôs constellation), which is famous for rain. While we did use some artificial showers, most of the on-screen rain is natural. The budget for this film was Rs 35-40 lakh. I made Pistulya with just Rs 15,000. The rain I pre¬≠sented was what I imagined.

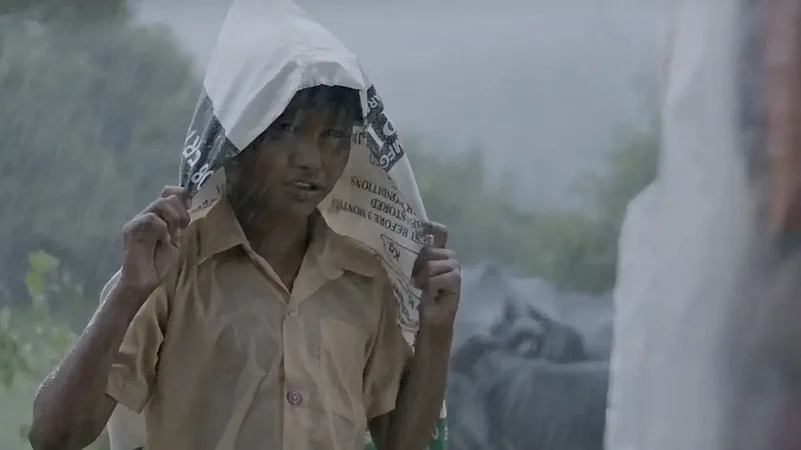

There isn바카라ôt much rain where I come from (Ka¬≠r¬≠mala, Solapur, Maharashtra). My father wou¬≠ld break stones. That was our source of inc¬≠ome. Once it rained, he was out of a job. My mot¬≠her would curse the rain. Everyone around us eagerly awaited the showers, but my mother was unhappy. In my adolescence, I chased the rains and travelled across western Mahara¬≠sh¬≠tra. Then I realised the difference between the one who experiences rain and the one who observes it. Also, the ones who face rain in torre¬≠nts have an experience different from tho¬≠se of us who visit these places as tourists. The latter바카라ôs approach is exotic, romantic. Even those who are suffering from the rains are observed as wonderful. This pisses me off. A toiling farm wor¬≠ker is presented with idyllic imagery. In my film Paa¬≠vsacha Nibandh, you will see that towa¬≠rds the end, students asked to write essays on rain as homework write about rain through the lens of the observer, not the experienced. The protagonist, Raja, is actually working thro¬≠ugh the rains, while those observing his toil wri¬≠te on the rains by looking at Raja. Everyone else writes about rains, but Raja lives the rain. Hen¬≠ce, he carries that experience in the wet note¬≠book.

You are among the few feature directors who continue to make short films, which inevitably win national awards.

My first film, Pistulya (2009) was a short. The short film offers me more independence to tell stories. There are no limitations, as is the case with feature films, where commerce demands that the real story begins at 80 minutes. Short films are like poems. You recite it and are done.

Why rain?

We바카라ôve had a one-way interpretation of rain. When a teacher asked my class what their favo¬≠u¬≠rite season was, 90 per cent mentioned the rai¬≠ny season. The rest said winter. I was the only one who stood with summer. I have no qua¬≠lms with summer; in fact, the kind of work I did in summer, and the life I have lived, has left me with nos¬≠talgia for summer. I have no objection to rai¬≠ns, but there is too much of love for it around us. Growing up, even I was swayed by this romantic¬≠ism, and wrote a poem on this. But when I matu¬≠red, I realised there was some ghot¬≠ala (scam). Tha¬≠t바카라ôs when I began looking at it with a critical eye.

The film also has a strong woman in Raja바카라ôs mother.

Women have always been at the centre of tolerance and everything we do. She might be upset with you or her condition, but she has love in the next moment. As a wife, she might kick the husband for his habits, but also ensures he doe¬≠sn바카라ôt fall ill and cares for him. The drunkard father is also not a villain. He is drinking out of compulsion and the pressure of trying to keep the family going.

Let바카라ôs talk about film aesthetics.

Aesthetics are false inspirations, curtailing our true experience. It forces us to find beauty in everything. Under the influence of constructed aesthetics, we바카라ôre forced to bring grandeur to rivers, lakes, mountains, etc. If aesthetics only rely on optimism, who will talk about those parts of the narrative that are not studied?

Are you talking about pessimism?

We optimise pride to a full scale. It becomes sloganeering without addressing the immediate needs of a person, like hunger. Pessimism comes across as a term that is berated if looked at through the traditional lens. Satyajit Ray, for example, worked with the theme of 바카라ėrealism바카라ô. His films don바카라ôt hype aesthetics. Yet, aesthetics is seen to represent negative, sombre films. This, in my view, is practical optimism. These films represent the real. People aim to come out of their condition to change it for the better. This is realistic optimism. You will see that in Paavsacha Nibandh, where Raja바카라ôs practical experience is not taken as a measure of talent. This is what makes realistic optimism.

Status of short films in India.

There aren바카라ôt many viewers in India, but short-film makers are still emerging. People have seen my works and of Umesh Kulkarni, and are now convinced that it바카라ôs a good enough genre to work in. Recently, I was invited to inaugurate a short-film festival on the occasion of Shahu Maharaj Jayanti in Jaysingpur, Kolhapur. It had 250 entries. The quality might differ, but there is an emerging trend.

Any cultural projects with a social angle?

I바카라ôve never made films with a commercial objective. Luckily, they turned out to be commerci¬≠a¬≠l¬≠ly successful so far. Sairat, for example, had a good run. But I also focus on issues. As you have mentioned, if we don바카라ôt say it, who will? Even Jhund is commercial, but I did it because I had it in my mind. I want to do films that are in my mind.

My focus is human. Pain is common to everyone. There is no caste, religion, nat¬≠ion or gender in this experience. If you read G.A. Kul¬≠k¬≠a¬≠rni or Chekov, you will feel the character and get bound by that pain. I keep thinking I바카라ôll do something about this at some point. My production house, Aatpaat, has to balance commerce and personal interest.

Do you recall us discussing anti-caste schools with Pa Ranjith while travelling in New Hampshire?

Yes, I have that in mind. I am learning now. Once I am ready, I바카라ôll solicit help from you and Lalit Khandare to execute the ideas. If you and others join forces, we can do it in a grand way. I will tell you about art and especially about fil¬≠ms. It attracts almost everybody. Everyone wan¬≠ts to become Manjule but not Yengde, as films attract easily. Now that you too have gla¬≠m¬≠our attached to your name, they also want to become like you.

Suraj Yengde Is an academic based at Oxford & Harvard, activist, and author of the forthcoming book Caste: A New History of the World

(This appeared in the print edition as 바카라ėRains Are Different for Those Who Experience it, and for Those Who Observe It바카라ô)