There is a growing tendency for oral comments and observations made in the course of court proceedings by judges of our constitutional courts to echo popular sentiments, instead of stemming from any legal principle. This is perhaps a good time to pause and reflect on where we are today, how we got here and where we are heading.

On April 27, 1959, Sylvia Nanavati confessed to her husband, Naval Commander Kawas Manekshaw Nanavati, that she was having an affair with businessman Prem Ahuja. Nanavati dropped his wife and children at a cinema theatre and proceeded to his ship, where he obtained a service revolver and six cartridges. He then drove to Ahuja바카라ôs house, confronted him and fired three shots at him with his service revolver, killing him instantly. Nanavati then surrendered before the police and admitted to having killed Ahuja.

The case gained intense media attention, owing to the dramatic elements of infidelity, honour and revenge that it involved, and public sentiment swung wildly in favour of Nanavati as the wronged husband who avenged an attack on his honour. Upon trial, a nine-member jury returned a verdict of not-guilty by 8:1 and acquitted Nanavati. Finding the verdict to be driven by public sentiment and personal biases of the jurors, rather than legal considerations, the Bombay High Court overturned the verdict and sentenced Nanavati to life imprisonment. The Supreme Court dismissed the appeal and upheld the decision.

Although Nanavati was eventually granted pardon by the then Governor of the Bombay Presidency in exercise of her constitutional powers, the case became the occasion for a relook by the 14th Law Commission headed by M. C. Setalvad into the viability of jury trials in India. The Law Commission recommended abolition of jury trials and consequently, it did not find place in the Criminal Procedure Code, 1973. One of the reasons cited by the Law Commission was by borrowing the words of Lord Alfred Denning that the system does not work in countries with a 바카라úmobile temperament, easily moved to pity or hate바카라Ě.

The Law Commission operated on the (fairly well-founded) premise, quoting Mahatma Gandhi where he had said in opposition of the system of jury trials, that, 바카라úIn matters where absolute impartiality, calmness and ability to sift evidence and understand human nature are required, we may not replace trained judges by untrained men brought together by chance. What we must aim at is an uncorruptible, impartial and able judiciary right from the bottom.바카라Ě

The purpose of this flashback was only to emphasise that we abolished the system of jury trials to escape decisions swayed by public sentiment, and this is how we have arrived today in a system where decisions are rendered solely by trained judges. However, the obvious flaw in the reasoning of Gandhiji quoted above is that it rests on the 바카라ėabsolute impartiality바카라ô and 바카라ėcalmness바카라ô of judges, their immunity to popular sentiment, if you will. It is for this reason that the 바카라ėRestatement of Values of Judicial Life바카라ô issued by the Supreme Court on May 7, 1997, to guide the conduct of judges lay emphasis on the need for judges to refrain from entering into public debate or expressing their views in public, except through their judgements, which must be self-explanatory. Judges are also not permitted to give interviews to the media.

Needless to say, this is an unrealistic ideal and its success must be judged not by absolutes, but by degrees to which it can be implemented and the constancy of efforts to strive towards it. One of the challenges in striving sincerely towards this ideal has become the system of virtual participation in courtrooms through virtual conferencing and through 바카라ėlivestreaming바카라ô of certain important matters by high courts and the Supreme Court.

What we are now witnessing was always going to be the inevitable consequence of livestreaming and virtual participation of the public.

Open justice is a principle enshrined in both civil and criminal procedure, and Section 153-B of the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908, and Section 366 of the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita, 2023, (Section 327 of the erstwhile Criminal Procedure Code) that prescribe that courts where a case is tried will be deemed to be an open court to which the public generally will have access. This was subject, of course, to the power of the judge to order in particular cases that the trial will be held in-camera. While media reportage of cases was common even in Nanavati바카라ôs time, this saw a boom from 2010-20 with the birth of news portals dedicated to reportage of court proceedings and 바카라ėlive tweeting바카라ô of hearings by some young lawyers who built an identity for themselves as court commentators. Technology and the decisions of the Supreme Court then expanded this principle of open justice to include participation in court proceedings through virtual conferencing.

Introduced on a war footing in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic to allow the justice system to continue to function through the lockdown, and thereafter continued to reduce crowding in courtrooms to mitigate the risk of infection, the system of participation through video conferencing was continued even after COVID-19 abated, with the then Chief Justice, D. Y. Chandrachud, by his order dated October 6, 2023, in Sarvesh Mathur v. The Registrar General High Court of Punjab and Haryana, directing that no high court or tribunal will deny access to video conferencing facilities or hearing through hybrid mode to any member of the bar or litigant desirous of availing such a facility.

In addition to participating in court proceedings through video conferencing, which still requires a link to join the proceedings and allows access for only a finite number of participants, the Supreme Court in Swapnil Tripathi v. Supreme Court of India directed that livestreaming of court proceedings in appropriate digital format forms part of the constitutional right to access justice or the right of 바카라ėopen justice바카라ô. The court directed the project of livestreaming of cases to be implemented in phases, and to begin with, only cases of constitutional and national importance being argued before the Constitution Bench were to be livestreamed as a pilot project. The stated goal was that eventually, all court proceedings before the Supreme Court will be livestreamed on the internet and/or radio and TV through an official agency such as Doordarshan. In the words of Chandrachud, 바카라úSunlight is the best disinfectant바카라Ě and livestreaming will impart transparency and accountability to the judicial process. So this is where we are today, where live court proceedings are available for viewing on the click of a button or the tap of a touchscreen.

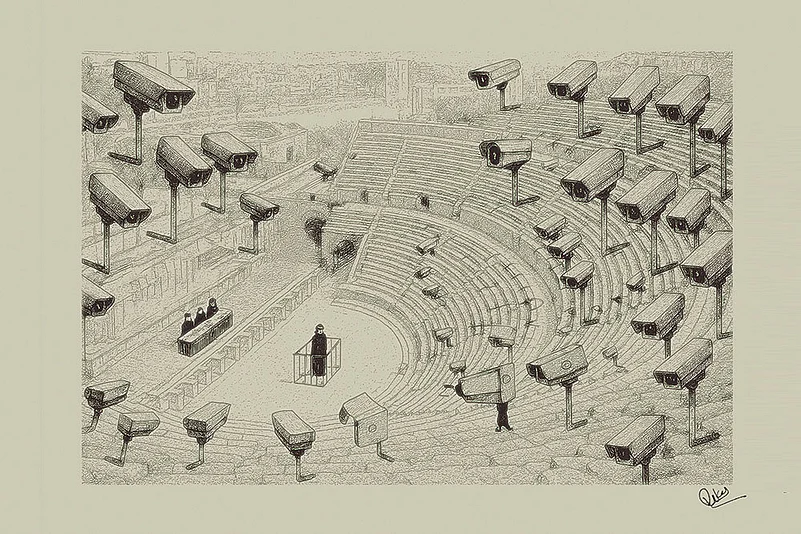

What we are now witnessing was always going to be the inevitable consequence of livestreaming and virtual participation of the public at large바카라Ējustice as a performance. Judges are, after all, people. Not only do they share a lot of the same biases that the average randomly selected individual may suffer from, since the judges of our constitutional courts are predominantly upper caste, predominantly upper class and predominantly male, a lot of these biases are also the dominant biases of society. So when public sentiment sways in a certain direction, chances are that the judge바카라ôs own sentiments are also along the same lines. The judicial system, in any case, places upon them the burden of rising above those biases바카라Ēby no means an easy task. Add to that a live audience that is baying for its own vigilante idea of justice to be delivered, an idea that the judge intuitively shares, but must strive to rise above, and it becomes more and more unrealistic to expect judicial outcomes that are indifferent to the expectations of the audience.

In this era of reality shows, where people are happy to watch other people cook, navigate romantic relationships, sing, dance, pitch business ideas, go hiking or simply try to live together in a house, a reality show where justice is delivered is more captivating than most shows. How long can it be before justice comes to be driven by TRPs? The audience is clear about what kind of justice it wants to see delivered. They want to see heads roll for the 26/11 attacks, for the rape and murder of Nirbhaya, for the Parliament attack, for the Bombay blasts, for the Nithari murders, and for a dozen other crimes that caught their imagination. They are convinced that Aarushi바카라ôs parents murdered her, that Surendra Koli and Moninder Singh Pandher were the women and children killers of Nithari, that Salman Khan was driving the car. No amount of legal argument, no alibi, no shortfall of evidence can sow reasonable doubt in their minds. They will cheer if they get the justice they want, jeer and fault the judge if they don바카라ôt. It is hard enough for judges to remain indifferent to these expectations as it is, and to expect them to do so before a live audience is to stretch legal fiction beyond breaking point. Would the judges who upheld and applied strict legal principles in the face of popular sentiment in Nanavati바카라ôs case have been able to do the same while holding court in an amphitheatre with a live audience?

And not just judges, lawyers too are playing more and more to the audience, looking to gather limelight and make political speeches in court because the court proceedings have more viewership than their personal social media handles can ever aspire to. Law students are taught the legal principle that 바카라ėjustice must not only be done, it must be seen to be done바카라ô. But this is more than justice being seen to be done, it is justice being done to be seen; and that has implications for the quality of justice itself. It is going to mark a turn towards a more populist idea of justice.

So if you feel that comments and observations being made by judges in court are sounding strangely like being reprimanded by your neighbourhood uncle for being too insensitive, too vulgar or too disrespectful, it is because your neighbourhood uncles are watching and their opinions are playing on the mind of the judges. And these are judges trained in the old school who have lived their lives striving to ignore the chatter outside the walls of their courtrooms; so for them the virtual audience is still less than real and they are still, by and large, driven by judicial habits formed over decades. One shudders to think how things will change with each passing year as the generations that have grown up with 바카라ėlikes바카라ô and 바카라ėshares바카라ô as the most valuable commodities in their lives move closer and closer to the bench.

(Views expressed are personal)