바카라úThe myths of a people are a record of their dreams and their sorrows, an inerasable register of their most deeply cherished and highly rated desires and aspirations as well as of the inescapable sadness that is the stuff of life and its local and temporal history.바카라Ě

Found in 바카라úRama, Krishna and Shiva,바카라Ě Ram Manohar Lohia바카라ôs wild essay from the mid-1950s, these prefatory words clarify the socialist leader바카라ôs care for the mythological life of communities before inaugurating a rare, original effort at evolving a civilisational self-portrait as well as a political philosophy through a delineation of the differing personalities of the three gods. A similar aim is pursued elsewhere in his writings via the figures of Draupadi, Sita and Savitri.

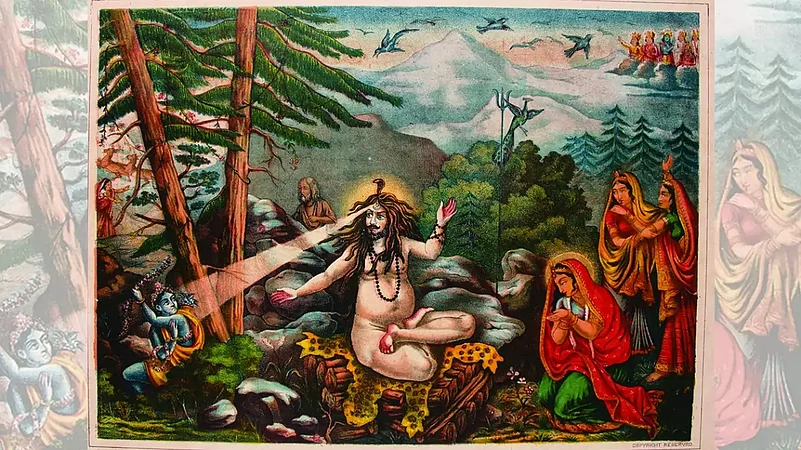

Rama and Krishna, Lohia reminds us, 바카라úled human lives,바카라Ě whereas Shiva was 바카라úwithout birth and without end.바카라̬† Characterising the formless (nirakara) and attributeless (nirguna) Shiva as 바카라ėnon-dimensional바카라ô, he points out that he is both¬† infinite and a part of events occurring in time.

The compassionate side of Shiva holds great appeal for Lohia. After destroying Kama for disturbing his meditation, he is moved by Rati바카라ôs sorrow at her husband바카라ôs death and restores his life.¬† Shiva바카라ôs intense love for his wife, Sati (Lohia ref¬≠¬≠ers to her as Parvati), also stands out for the socialist thinker.¬† His mourning at the death of his beloved wife takes on a demonic character: placing her corpse over his shoulders, he kept walking until her body fell off part by part across different regions of the country. 바카라úNo lover, nor god, nor demon, nor human,바카라Ě Lohia remarks with amazement, 바카라úhas left such a story of stark and uninhibited companionship.바카라Ě

Shiva바카라ôs actions exemplify Lohia바카라ôs principle of immediacy, which asks that moral justifications be found in the immediate steps one has taken, instead of seeking them in either past actions or future outcomes. Taking the morally most appropriate stand in the present without letting the past or the future haunt it, for him, is absolutely essential.¬† Lohia바카라ôs discussion of immediacy wishes, of course, to break free from liberal and Marxist utopian projects that justify their political action in the present by alluding to future outcomes as well as the revivalist politics of religious fundamentalists that justify revenge-seeking in contemporary times by referring to actual or imagined deeds in the past.

Holding up Shiva as 바카라úthe embodiment of the principle of immediacy바카라Ě, Lohia further notes that he is 바카라únot guilty of a single act which can indubitably be described as without justice in itself 바카라¶ Every one of his acts contains its own immediate justification and one does not have to look for an earlier or later act바카라Ě.

In the famous Puranic episode of the gods and the demons churning the ocean to get nectar, Shiva, who had no part in the war between these two rivals or in their collaborative wish to find immortality through nectar, stepped in to drink the poison emitted from the ocean and saved everyone. His actions, Lohia adds poignantly, 바카라úlet the story proceed.바카라Ě Again, when a devotee wanted to offer worship only to Shiva and not to Parvati, his consort, seated beside him, Shiva turned into Ardhanarishvara, part-woman and part-man, in response. If these two episodes reveal for Lohia the exemplary style of Shiva바카라ôs moral interventions, two other actions proved less easy for lohia to justify through the principle of immediacy.

When Shiva cut off an elephant바카라ôs head to revive the decapitated Ganesha and console his mother, Parvati, didn바카라ôt the elephant바카라ôs mother suffer from grief? Lohia바카라ôs response: 바카라úIn the new Ganesh, both the elephant and the old Ganesh continued their existence and neither died.바카라̬† Further, this new being, which meant continued life for both Ganesh and the elephant, went on to prove to be of 바카라úperennial delight and wisdom [바카라¶] which only a comic mixture of man and elephant can be바카라Ě.

The other difficult episode for Lohia is the dancing match between Shiva and Parvati at Chidambaram. Excelling at dance, Parvati had nearly outdanced Shiva, when the latter raised his leg up high, a move that considerations of modesty made difficult for Parvati to match. Shiva won as a result. Did he lift his leg high merely to defeat Parvati? Or, Lohia wonders further, was his move 바카라úthe result of a natural crescendo of a dance of life that was warming up step by step?바카라Ě. Since 바카라úThe dance of life consists of bumps which a squeamish world calls obscene and against which it tries to protect the modesty of its women바카라Ě could Shiva have invited Parvati to break the moral limits, in the aesthetics of dance as well as elsewhere?

Lohia stayed an atheist till the end of his life, but his great curiosity about the mythological inh­eritance of India was firmly  in place all along.  Unlike other atheists, who prefer either to stay indifferent towards religious symbolism or strive to demystify it or dismiss it as so much irr­ational cultural baggage, Lohia thoroughly reli­shed it without feeling obliged to believe in it. He sought in it clues to the cultural psychology of Indians. And, in a display of a still-uncommon creative intellectual relationship with the symbolic heritage of the country, he evolved interpretive means from it to aid in the better understanding of Indian society.

Lohia바카라ôs engagement with the mythological wor¬≠lds of non-Hindu faiths and indeed those of Shu¬≠dra, Dalit and tribal communities was insufficient. One can only wonder about what else he might have offered had this detail been otherwise.

(This appeared in the print edition as "More than a Mythical persona")

(Views expressed are personal)

Chandan Gowda is Ramakrishna Hegde chair professor of decentralisation and development, Institute for Social and Economic Change, Bangalore.