Not far from the Sharjah Art Museum, one of the main venues of the 16th Sharjah Biennial, an inconspicuous storefront in the local souk bears the name 바카라Photo Kegham바카라. A gridded presentation of black-and-white photographs makes it unlike any other shop in the lane. Doing a double-take before checking the guidebook reveals it to be one amongst the many small and large display spaces spread across the Emirate. The street level exhibit pays homage to the first photography studio in Gaza, Palestine, set up by Kegham Djeghalian Sr. in 1944 before the first Nakba in 1948 changed the landscape of the region.

An expanded archive, retrieved by his son and housed in the museum for the duration of the biennial, shows a milieu of beautiful faces, some staged portraits and others family photos, weddings, a costume party, and other candid moments of celebration. It is deeply nourishing to witness these smiling faces, this joy of lives lived in fullness, especially after 18 months of war-torn images. Yet, it is simultaneously heartbreaking to be confronted with the weight of all that Palestinians have lost over these decades of occupation.

The 16th Sharjah Biennial, running until 15 June 2025, gathers multiple artworks and archives like these which challenge structures of the 190 artists바카라 native contexts across the globe. The biennial garnered substantial buzz when it was announced that five curators from the Global South바카라Natasha Ginwala (Artistic Director of COLOMBOSCOPE, Colombo), Amal Khalaf (Director of Programmes, Cubitt, London and Curator at Large, Public Practice, Serpentine Galleries, London), Zeynep Ăz (independent curator, Istanbul and New York), Alia Swastika (Director of the Biennale Jogja Foundation, Yogyakarta) and Megan Tamati-Quennell (New Zealand-based curator of modern and contemporary MÄori and indigenous art)바카라would lead this edition. All of them are well-established in their own right, setting up infrastructure in their regions, driving long-running commissions, and promoting discourse around underrepresented artists. It speaks to the ethos of their practices that this exhibition destabilises the US-European male-centric canon, foregrounding women and indigenous practitioners across art forms.

With little or no experience of working together, the five curators had less than two years to put together a mega exhibition that coalesced their visions together. What results is a self-proclaimed "open-ended proposition" under the title "To Carry", a theme further evoked through an array of addendums, "to carry a home, to carry rupture, to carry new formations바카라Š" Moving through the 16 venues across the Emirate it is apparent that the curators determinedly carried their individual practices to the table, with commendable resolve not to end up with five separate exhibitions.

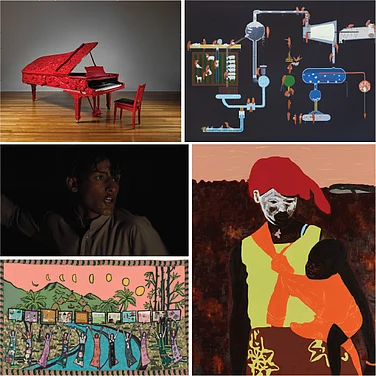

The works range from emotive installations, to archives of socially-reciprocal practices, to tessellated material economies, and beyond, thematically forming many constellations of reverberance, with a few questionable arrangements. However, it is most often the disparate exhibition design that unsettles the sensorial experience. In this arrangement one gets the feeling of being invited to a dinner party with a lush spread of multiple cuisines. Although it is sometimes confusing for the tastebuds, the food itself leaves a delectable taste.

Of particular delight for enthusiasts of Indian art history are two mini-retrospectives of abstract painter Vishwanadhan and dancer-choreographer Chandralekha curated by Natasha Ginwala as part of her project. Both presentations look at interdisciplinary contributions by the artists over many decades of their lives, brought together by extremely thoughtful exhibition design. Rhythmic and vivid, Kerala-born, Paris-based artist Vishwanadhan's canvases draw you into their layered explorations of sacred geometries. Alongside, a non-narrative film made in collaboration with Adoor Gopalakrishnan shows the multi-pronged approach of the artist's inquiries. Incidentally, the film also features pioneering dancer, choreographer and writer Chandralekha, whose posthumous

archive is on view in another location. Situating her practice as a philosophy of movement and cosmic time-keeping, Ginwala brings together a collection of largely unseen video recordings of dance productions, as well as interviews, writings and rehearsal photographs, joined in conversation by a newly commissioned solo performance titled Nyasa by Tishani Doshi, who trained under Chandralekha for many years.

The currents of oceanic paths, pivotal to Sharjah's prosperity, recur across the curatorial threads, appearing as submerged histories, more-than-human narratives, and counter-strategies for planetary survival. Many works resuscitate wounded archives such as Shivanjani Lal's I Felt Whole Histories honouring the journey of her community, forced to migrate from India to Fiji as indentured labourers on sugarcane plantations; a history largely unacknowledged in the sub-continent. 87 plaster-caste sugarcane stalks hauntingly placed across the room mark the number of ships that travelled across the two locations. Adelita Husni-Bey's tactile video installation drawing from her dense research into the politics of water as a weaponised commodity leaves a strong imprint. Like a Flood reflects on the disruption of Libya's water supply during Italian rule, weaving together poetic interviews with climatic analyses, arranged alongside two large concrete water pipes that double up as viewing stations.

In this context, it is hard not to think about the famine in Gaza, sustained by Israel's atrocious blockage of water and humanitarian aid. Unlike many other countries that disallow state-funded conversations around Palestine, the presence of these narratives is bountiful. Along with "Photo Kegham", another emotionally charged presentation is that of Mohammed Al Hawajari and Dina Mattar who returned to the rubble of their house to salvage the vivid paintings on display (The Eltiqa Collective, which the two artists are a part of, is also having a stellar survey show at the Jameel Arts Center in Dubai). While the biennial determinedly platforms such artworks, there is not a single artist from Sudan, whose government has alleged the United Arab Emirates' (UAE's) links with the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces, including the supply of weapons. A lyrical performance by the Sudanese-diasporic group One Sudan One Sound of Solidarity was also cancelled without any statement.

A few of the other works subtly critique inequalities in the region. The Al Madam village, buried under sand, speaks to the prospect of experiencing artworks in unexpected environments, one of the pleasures of visiting a biennial over a museum exhibit. This overrun landscape comes alive with a sonic artwork by DineÌ artist Raven Chacon. Originally intended as a relocation site for a Bedouin tribe but never inhabited, the houses have been almost fully occupied by small sand dunes. Peering into the surreal interiors, viewers are caught by surprise as snippets of Bedouin songs relay through the dozen buildings. Bringing back the voices of the Bedouin into the fraught conversation around indigeneity and hyper-development, this piece by Chacon is one of the few in this edition of the Sharjah Biennial that provokes internal fault-lines within the UAE.

In her colossal installation, Gastromancer, Monira Al-Qadri smuggles queer literature into the UAE where LGBTQ+ people live under the fear of persecution. An orange glow sets the stage for an encounter with two larger than life seashells, transporting one to an esoteric realm where possibilities exist beyond the narrow confines of social norm. The sculptures take from the shells of the murex mollusk, whose female species has been reported to change sex due to contamination from oil industry affluents. On moving closer, two androgynous voices emanate from within. They recall a story of accidentally changing genders while swimming in the ocean, a text adapted from the once-banned book The Diesel (1994) by Thani Al-Suwaidi, featuring a gender non-binary djinn growing up in the neighbouring Emirate of Ras Al Khaimah.

In the Old Al Diwan A Amiri, a former 'ruler's court', powerful visions for a new future are proclaimed. Subash Thebe Limbu weaves a non-linear timescape drawing from Yukthang (Limbu) philosophy in Eastern Nepal and his proposition of Adivasi Futurisms. His sci-fi film Ladhamba Tayem; Future Continuous opens us up to visualise progress and tradition not as antagonistic, but rather as feeding into each other, necessarily entwined for the possibility of justice. Luke Willis Thompson transports us to Aotearoa New Zealand in 2040, where a new constitution for an indigenous pluri-national state is being announced. Emphatically delivered in Maori by Oriini Kaipara, the video lambasts the deceitful nature of colonial treaties, declaring a renewal of compassionate self-determination rooted in the Maori worldview, "whoever you are, if you are on this land, you will be sheltered and cared for." The large participation of indigenous artists in this biennial feels imbued with agency rather than tokenism, a shift which might be attributed to influence of Maori curator Megan Tamati-Quennell, underlining the need for underrepresented practitioners across all levels of creative work to manifest supportive infrastructures.

Recalling Sara Ahmed, 바카라feminist work is often the work of holding things together, fragile things, the pieces of something,바카라 it seems fitting that only seasoned feminist practitioners could have made a soulful biennial that flows together while holding the multiplicious intentions and worldviews of its curators. In the resonances and disjunctures that conjoin the five curatorial threads, what emerges most strongly is a reminder of the chaotic reality of meaningful collaborative labour; of solidarity as a practice of staying together, in disagreement, celebration and aftercare. Those of us who see the need to build new institutions that do not perpetuate ingrained systems of violence must instate value in this messy work of gathering, nourishing, mending and co-visioning that is all too often rendered invisible by the shadow of object and spectacle.

(Shaunak Mahbubani is a curator-writer based between Berlin & Mumbai)