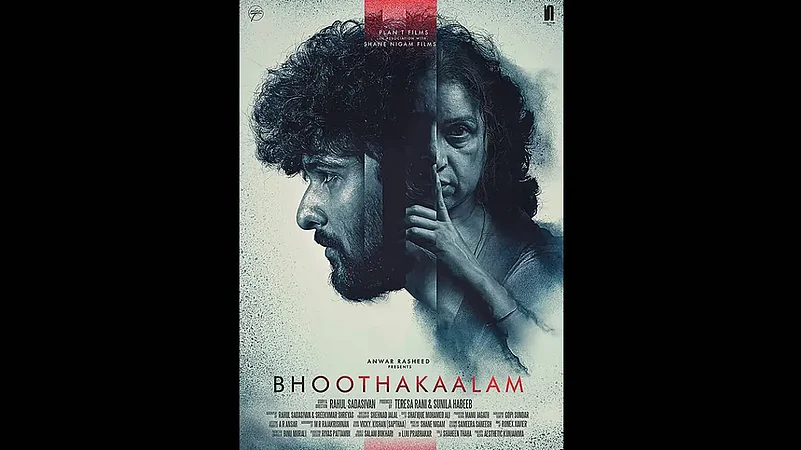

If you like your horror cinema to be easily classified바카라Ēthe common categories include 바카라úpsychological바카라Ě vs 바카라úsupernatural바카라Ě, or 바카라úquietly creepy바카라Ě vs 바카라úfull of jump scares바카라Ě바카라Ēyou might be intrigued by the Malayalam film Bhoothakaalam, about a middle-aged woman and her son battling personal demons. In tone, setting and characterisation, this is a subdued work rather than one of expl¬≠i¬≠cit terrors. Asha (Revathi) and Vinu (Shane Nig¬≠am) seem afflicted by a sadness, the causes of which aren바카라ôt spelt out, though we grasp thi¬≠ngs about their past and present바카라Ēa husband/father who died, leaving behind unhappiness and debt; a boy who misses him and sees his mother as clinging; a woman who can바카라ôt conc¬≠e¬≠ive of life without her son.

But while Bhoothakaalam maintains its gro¬≠unded tone, it also has things that go bump in the night바카라¶ and there is a haunted house too (albeit, in a bright residential area, far from the archetype of the isolated mansion). Without giving away too much, midway through the narrative there is a slight shift in our percept¬≠ions about what is going on, and a sense that subtle and supernatural can go together.

바카라úIsn바카라ôt it just a house?바카라Ě someone says when the possibility of demoniac spirits comes up, 바카라úmade of stones, cement, mud, wood.바카라Ě But what if a brick-and-mortar entity can respond to the conflicts of the people living in it? In one tense dinner-table scene, as mother and son start to argue and voices are raised, the camera pointedly focuses on the window curtains in the background바카라Ēthey might be moving a little more than expected, or is it just the wind? Here and elsewhere, one gets the impression that the house is somehow feeding on their negative energies. Asha and Vinu have become distan¬≠ced from each other, and they need to rebuild their trust for the monster to be defeated.

Which means that like so many horror films, Bhoothakaalam is essentially about loneliness and alienation. 바카라úIf he leaves, who will I have? Won바카라ôt I be alone here?바카라Ě Asha asks in an early scene when it is suggested that Vinu travels els¬≠ewhere for a good job. There is an echo in her despairing words of the most famous horror film about an intense mother-son bond, Alf¬≠red Hitchcock바카라ôs Psycho, in which a young man is seemingly tied forever by an umbilical cord, unable to move away from his mother바카라ôs presence.

When I first watched Psycho as a shy adolesc¬≠ent living with a recently divorced mother, the film touched me in ways I couldn바카라ôt articulate. There was something so powerful about the sen¬≠se of decay and stasis, about the vulnerable awkwardness on Norman Bates바카라ôs face as he tri¬≠ed to express his feelings to a stranger. Or his indignant response to the accusation that he might be trying to leave the Bates Motel and sta¬≠rt a new life elsewhere. (바카라úThis place happens to be my only world. I grew up in that house up there.바카라Ě) Today I still spend much of my working day in the flat that my mother and I moved to in 1987, and Psycho is never far from my mind when I wander its empty rooms바카라Ēincluding the room she died in a few years ago. I think about how our living spaces can inhabit us as much as we inhabit them. ¬†

The horror genre offers plenty of room for ref¬≠l¬≠ections of this sort. Perhaps this is also why it is a surprise to learn, late in Bhoothakaalam, that Asha and Vinu had been living in their house for a short time, and on rent바카라ĒI had assumed it was an old family house where their entire personal histories had unfolded.

ALSO READ: The Ghost As A Metaphor In Bengali Cinema

Horror literature and cinema have long mined the idea of a haunted house as a mirror to the states of mind of the people in it바카라Ēfrom Shirley Jackson바카라ôs iconic novel The Haunting of Hill Hou¬≠se (about experiments in fear conducted by a doctor with a small group of people) to Step¬≠hen King바카라ôs The Shining (a writer takes up a position as the off-season caretaker of a large, sno¬≠w¬≠bound hotel and finds the place exerting a spell on him) to Sarah Waters바카라ôs The Little Stra¬≠nger (a family that was once well-off continues to stay in their crumbling estate). The filmed ada¬≠ptations of these works make visual or aural links between the ominous setting and the dark crannies in the inhabitants바카라ô minds. In the 1963 film The Haunting바카라Ēadapted from Jackson바카라ôs nov¬≠el바카라Ēa distorting lens suggests the oddness of the house바카라ôs spaces; Stanley Kubrick바카라ôs 1980 film The Shining uses long Steadicam takes that emphasise the agoraphobia-inducing vastness of the hotel.

Many modern horror filmmakers make a fetish out of being restrained and realistic, as if the¬≠re were something inherently distasteful abo¬≠ut making viewers jump out of their seats in the old way (or maybe it바카라ôs just that the popcorn is now so expensive that nobody wants to risk spilling it!).

ALSO READ: The 바카라ėSpirit바카라ôOf Filmmaking

But once in a while we still find fil¬≠ms like Jennifer Kent바카라ôs The Babadook (2014), which successfully operate in multiple modes. This is at one level a 바카라úcreature feature바카라Ě바카라Ēthe half-¬≠glim¬≠psed bogeyman is as otherworldly as they come¬≠바카라Ē¬≠but the story바카라ôs heart is the relationship bet¬≠ween a protective single mother and her little boy whom others see as disturbed. Oth¬≠er acc¬≠laimed recent films바카라Ēfrom Ari Aster바카라ôs Midsommar and Hereditary to Jordan Peele바카라ôs Us and John Krasinski바카라ôs A Quiet Pla¬≠ce바카라Ē¬≠also get their bleakness, and in some cases their redemptive power, from strained filial relations¬≠h¬≠ips바카라Ēa young woman tries to cope with the sudden suicide-murder of her family, another family has to perfectly plan and synchronise its every action if it wants to stay alive in a dystopian scenario.

***

While the alienation theme can der¬≠i¬≠ve from complex parent-child relati¬≠o¬≠nships of this sort, there are other ways of being cut off from the 바카라únormal바카라Ě world. 바카라úI must have gotten off the main road,바카라Ě says Marion Crane, a you¬≠ng woman who finds herself at the Bates Motel after having escaped her home-town with stolen money. 바카라úNob¬≠ody ever stops here anymore unless they바카라ôve done that,바카라Ě replies Norman. Marion바카라ôs theft has led her, literally, into the 바카라úgalat rasta바카라Ě and a subterranean world.

ALSO READ: Resident Evil: The Zombie Apocalypse In Goa

The trope of the lonely or isolated woman has also fuelled many classics over the decades, goi¬≠ng back at least to Val Lewton바카라ôs 1942 Cat People (and extending forward through the 1970s and 80s to films targeted at male viewers, which cen¬≠tred on the voyeuristic thrills that came from seeing a woman in peril). In these stories, the protagonist might be alienated by circums¬≠t¬≠ances or personality, and dealing with some com¬≠bination of mental illness or societal repr¬≠e¬≠s¬≠sion. There are obvious subtexts, especially when the story is set in conservative framewo¬≠rks where it is seen as undesirable for women to be untethered (or 바카라útoo independent바카라Ě).

Thus the pregnant Rosemary in Rosemary바카라ôs Baby (1968) needs to be controlled by smiling neighbours who are really a satanic cult; they can바카라ôt allow her autonomy, she must be cut off from close friends who might form a support circle. In the poignant French film Eyes Without a Face (1960), a disfigured young woman wanders sadly around her large mansion while her surg¬≠eon father바카라Ēanother concerned but contr¬≠o¬≠lling parent바카라Ētries to restore her face. In the Jap¬≠a¬≠n¬≠ese classic Onibaba (1964), an old woman beco¬≠mes unhinged as she realises that she mig¬≠ht be abandoned by her daughter-in-law (they live alone in the grasslands, stealing from wou¬≠n¬≠ded samurai). And in one of my favourite B-¬≠mov¬≠ies, the cheaply made but very effective Car¬≠nival of Souls (1962), a woman named Mary emerges from a lake after an accident and, disoriented, tries to negotiate her surrou¬≠n¬≠dings. Is she literally dead바카라Ēa zom¬≠bie¬≠바카라Ē¬≠o¬≠¬≠r is her confusion an allegory for trying to make a fresh start and repeatedly coming up against dead ends?

It바카라ôs easy to imagine some of these lonely-people films in conversation across space and time. For instance, think of Roman Polanski바카라ôs Repulsion (1965), Pavan Kirpalani바카라ôs Phobia (2016), and Ram Gopal Varma바카라ôs Kaun? (1999). In each, a woman is in a confi¬≠n¬≠ed space, trying to make sense of her predicament. The specifics are different바카라Ēone character may be sexually repressed, another might be the caged victim of a domineering man, the third may be dealing with a menacing threat outside the house바카라Ēbut each of them is trying to keep monsters, real or imag¬≠i¬≠ned, at bay.

ALSO READ: An Allegory Written In Blood

But to my mind, the best horror film about loneliness and despair is one that doesn바카라ôt yet exist바카라Ēit is the never-made film version of one of the scariest, saddest books I have read, Helen McCloy바카라ôs Through a Glass Darkly. The story centres on this indelible idea바카라Ēa melanc¬≠h¬≠oly young woman named Faustina is faced with the possibility that she has a ghostly dopp¬≠elg¬≠a¬≠n¬≠ger, a shadow self that is impersonating her and getting her into trouble, and will eventually come to claim her soul. 바카라úIn early childhood,바카라Ě she muses, 바카라úYou stare at your face in the mirror and look at your hands and feet and say to yourself: I am me. I am not anyone else. Yet, somet¬≠h¬≠ing inside you goes on feeling that it바카라ôs not quite true.바카라Ě The book바카라ôs climax involves both this spe¬≠c¬≠tral double and a reflecting surface in a hou¬≠se¬≠바카라Ē¬≠a perfect depiction of inner and outer spa¬≠ces¬≠바카라Ē¬≠glass and cement and a tormented mind¬≠바카라Ē¬≠coming together to devastating effect. If there is ever a film of this novel, make sure to hold that expensive popcorn tub as tightly as you can.

(This appeared in the print edition as "Under the Skin")

(Views expressed are personal)

ALSO READ

Jai Arjun Singh is an independent critic and author