Bharat Aluminium Corporation (BALCO) was a profitable PSUÂ with 15 per cent market share when the Vajpayee government decided to disinvest it. In 1997, the Disinvestment Commission had recommended a 40 per cent divestment, but the government was looking at selling 51 per cent, a controlling stake, to private bidders바카라”the company was to be sold for Rs 551.5 crore.

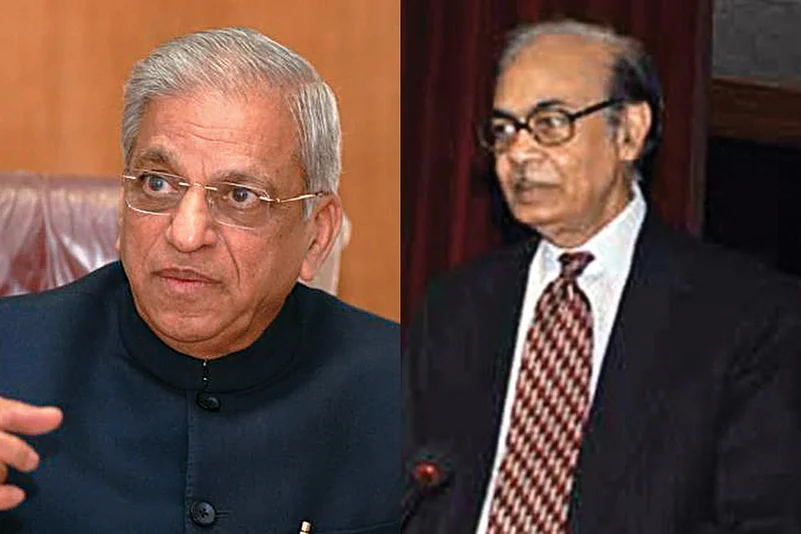

Just the reserves and surpluses of the PSU amounted to Rs 460 crore, a media report pointed out바카라”and nobody could explain why a property assessor had been asked to assess only the value of the fixed assets for the stake sale. BALCO was, after all, a company generating hundreds of crores of rupees in tax revenue, several crores in dividends and had bright prospects. Not only was the company profitable, but, with one of its mines located in Korba, Chhattisgarh, it also had a significant role in local development in the then newly formed state. Moreover, as the move바카라™s critics saw it, an undervalued and hasty disinvestment was not in the interests of BALCO바카라™s vast workforce. A PIL was filed before the Supreme Court, arguing it was an arbitrary and opaque decision and that the valuation was flawed. In December 2001, a bench of Justices B.N. Kirpal, Shivaraj Patil and P. Venkatarama Reddi refused to intervene in the disinvestment policy, saying that the 바카라ścourts are not intended to바카라¦nor should they conduct the administration of the country바카라ť.

Justice Kirpal noted that the courts shouldn바카라™t interfere in economic policy decisions except in two conditions: a constitutional or statutory violation or an illegality in the decision-making process. Such a view has found selective favour among other cases heard by the Supreme Court, which has also ruled on several economic policies바카라”for example, vis-Ă -vis the telecom industry.

In the BALCO case, the Supreme Court said, 바카라śValuation is a question of fact and the court will not interfere in matters of valuation unless the methodology adopted is arbitrary.바카라ť This was despite the fact that the PSU should have been valued at a much higher price before being sold. Instead, the apex court endorsed the government price since the stake in the company had been sold to the highest bidder, above the reserve price.

In 2006, the Comptroller and ÂAuditor General of India felt otherwise and noted that BALCO was grossly undervalued during its sale to the private company.