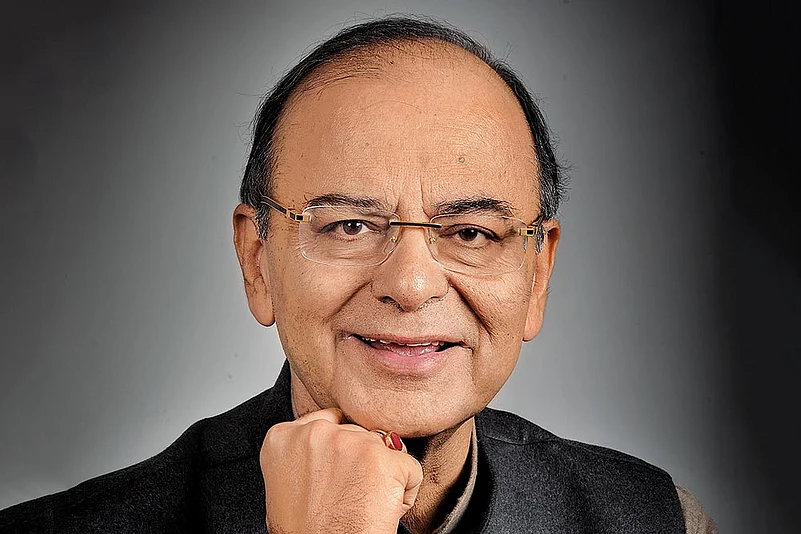

I first met Arun Jaitley in 1974, when we were both students at Delhi University바카라”he the president of the Delhi University Students바카라™ Union (DUSU), and I the president of the St Stephen바카라™s College Students바카라™ Union Society. DUSU was a stronghold of the ABVP, of which Arun was a leading light, and my union was resolutely non-political; St Stephen바카라™s did not permit any of the political parties바카라™ student movements to affiliate any student on our campus. Still, we got along well. I was 18, and he was just shy of 22, but the age difference quickly dissolved in mutual respect. To my surprise, he endorsed my candidacy for the academic council of the university, which elected one student representative; he told me that even if we did not see eye-to-eye politically, he felt a student of my accomplishments was what the council needed. (It is another matter that his support cost me that of many liberal and minority students who had showed up intending to vote for me, but changed their mind when they thought I might be the ABVP바카라™s candidate; as a result, this became the first of the only two elections I have ever lost!)

We parted company on the JP 바카라śTotal Revolution바카라ť movement, of which he was an entÂhusiastic supporter. Though I greatly admÂired JP, and privately attended a hugely impÂressive discussion in his favour at the Gandhi Peace Foundation, I stuck to the Stephanian line that my union would remain non-political, and refused to overtly support the movement. Later, when the Emergency came and Arun, like many other student leaders, was detained, I wondered whether I had done the right thing.

By then I had gone off to graduate school in the US, and followed the nation바카라™s politics from afar; three years later I joined the UN, while Arun emerged as a smart and successful lawyer in Delhi and budding politician, as national president of the ABVP. We were not regularly in touch, but on my visits to Delhi, mutual friends, notably Chandan Mitra and Raian Karanjiwala, would host dinners for me to which they invited Arun, who was close to both of them. As a result,

I developed a personal fondness for him quite distinct from my increasingly vehement disagreement with his political views. This persisted when I finally returned to India at the end of my UN career and joined politics. Though we were now on opposite ends of the political spectrum, we resumed a cordial friendship. I dropped in to see him once in a while, even when I was a Union minister and he was leader of the Opposition, and he returned the compliment. When my wife passed away, he came home and spent an hour with me as I sat bereft, shell-shocked and inconsolable.

Arun was the consummate Delhi insider, a sought-after guest at every Delhi soiree and perfectly at home in all sorts of company. He was a bon vivant, clever and witty in conversation, with a twinkling-eyed taste for gossip and an intimate knowledge of the foibles and peccadilloes of every notable denizen of Lutyens바카라™s Delhi, which he enjoyed recounting with relish. (Sometimes, it must be said, I did wonder what he was saying about me behind my back, so effectively did he skewer people I thought were his friends.) His frankness was leavened by his accessibility to all: non-political friends and media loved him. No wonder he was known as 바카라śevery non-BJP person바카라™s favourite BJP person바카라ť.

Arun and I had other interests in common, notably cricket. As a prominent cricket administrator, he knew more about how the game worked in India than most. He was wise and insightful about global trends: when I was still at the UN, he told me that India바카라™s position in the International Cricket Council was equivalent to the United States바카라™ in the UN Security Council, a parallel I found revealing and eye-opening. As a parliamentarian, he was superb: it was a pleasure questioning him in the Lok Sabha because his answers were both knowledgeable and precise. When my party gave me the honour of speaking in debates on his budget proposals, I could be sure he would respond effectively to the arguments he could rebut, while cheerfully ignoring those he had no answer to.

My last conversation with him was when he had just been taken ill again but was at home, and I asked when I could come by to visit him. He said he was grateful for the call but was not up to receiving many visitors, and said we would meet before long. That day never came.

With Arun바카라™s passing, the nation has lost a fine public servant, a minister of rare distinction and a man whose interventions바카라”whether in speeches or blogs바카라”made significant contributions to the natÂional discourse. The BJP, too, has lost one of its few public figures who could reach easily across the aisle and appeal to constituencies who were not considered 바카라śnatural바카라ť supporters of the party. His talent for conciliation and comradeship, transcending ideologies and political loyalties, will be sorely missed in our increasingly polarised politics.

The BJP has now lost five leaders and ministers in their prime: Ananth Kumar at 59, Anil Dave at 60, Manohar Parrikar at 63, Sushma Swaraj at 66 and now Arun Jaitley at the same age. It is a sobering realisation of how much politics and governance takes out of people at their peak, and also how depleted the senior ranks of our ruling party have becÂome. India could ill afford to lose Arun Jaitley, and all patriots will mourn his untimely departure.

(Writer is the Congress Lok Sabha MP for Thiruvan-anthapuram, a former Union minister and diplomat)