Myajlar is one of the last towns on the Jaisalmer border, which, at 464 km, is one of the longest that India shares with Pakistan. The village was one of the key locations for the 1965 Indo-Pak war. Villagers who are old enough remember watching Indian army tanks ploughing through their kachchi roads.

With no more than 2,900 people, Myajlar sits at the edge of the Indian Thar desert border. In summer, the wind blowing across it only contributes to the dry, harsh heat. Temperatures exceed 50° C in the day. 바카라It only rains once every two-three years here,바카라 says Jeetu Singh, who is the de facto sarpanch of the town. Singh바카라s sister-in-law is the sarpanch but he takes care of most of her responsibilities, he explains.

This is the land of camel tracks and shifting sand dunes, of craggy rock plateaus and salt-encrusted lake beds바카라an inhospitable environment that is impossible to navigate, let alone live in for all but the hardiest. And that is what the people who live here claim to be.

바카라Life in border towns is definitely tough, but the people are hard workers. If they could find work, they will go above and beyond to fulfil it. They aren바카라t scared of hard work at all,바카라 says Kasab Singh Sodha, a 65-year-old retired Sashastra Seema Bal (SSB) officer, who grew up no more than eight kilometres away from the Indo-Pak border in the village of Karda.

Here, in district Jaisalmer, entire villages descend from the one family. 바카라Everyone is related, our great-grandfather or mothers are the same and then the familial line diverges with marriages,바카라 says Sodha. He and his family have lived in Karda바카라known as India바카라s last village바카라for over five or six generations.

Their lives straddled the invisible line drawn in 1947, long before India put up the wire fences in 1971. 바카라Earlier there was no border,바카라 says 80-year-old Ranu Lal. 바카라When it rained, our herds would smell the grass on the other side and run there to feed. We would have to go a hundred kilometres to get them back.바카라

Lal, along with two other men from Myajlar, worked as guides for the army. However, most people here are dependent on whatever they can earn as herders of cattle and goats. Sometimes, like in the 1965 war바카라when Pakistan바카라s troops captured the villages around Myajlar and the town itself바카라they worked as the army바카라s supply chain, going to and fro to Indian army encampments with water and rations.

바카라The government had first said that they will evacuate the village but then the villagers themselves told the government, 바카라no, you fight, we are with you and we will fight alongside,바카라바카라 says Sodha, recalling stories his father told him. During the 1971 war, he was only a year old. 바카라In 1965 and 1971, both wars, our villagers aided the army in the fight,바카라 he points out. 바카라Our people helped a lot바카라we would take rations and water to the soldiers on camelback.바카라

Villagers would fill up large saddlebags 바카라바카라pakhals바카라바카라with water and rations for soldiers, load it on to their camels, and supply the army that was then fighting back Pakistani troops at the Jaisalmer border. 바카라Each pakhal can carry about 100 litres of water,바카라 explains Sodha.

Today, sharp wiring through which electric current runs at night, and floodlit poles cordon off India바카라s land on the boundary바카라the subcontinental country has fenced 2,064 of its 3,323 kilometres of border shared with Pakistan.

The bottom of Lal바카라s walking cane is iron-clad and clinks softly when he walks around his three-room home shared by ten people. He served as a scout in both the 1965 and 1971 wars, guiding troops into Pakistani territory, identifying Pakistani encampments ten to fifteen kilometres ahead of the army바카라s platoons. 바카라It바카라s dangerous work바카라that바카라s why I got recognition,바카라 he says, laughing and pointing towards his medals of valour.

바카라Daily we see our elderly dying for lack of medical care, our cattle dying for lack of water and fodder바카라Šwe face death every day that we live here.바카라

Lal recalls capturing soldiers alive, and also his lost comrades. Though the three scouts from Myajlar came back alive in 1965, they lost six army officers. One of them, Lance Havildar Deb Singh Bhandari, died while stopping an enemy machine gun. The village erected a remembrance monument for the six officers, and the others who followed in skirmishes during the 1971 war as well. But the memory has only made them bolder. 바카라Rajasthan doesn바카라t feel fear,바카라 says a proud P. Soni, who is assistant to the Jaisalmer district magistrate.

When word came to Lal of fresh tensions flaring up post the April 22 Pahalgam terror attack, he walked into the local Border Security Force (BSF) post, the police station, the army office바카라everywhere바카라with a letter: 바카라I am ready to be an army guide again.바카라

If he must die, he would prefer it to be on the battlefield, honoured, rather than quietly at his home. 바카라At least if I die serving my country, the government will give me salaami.바카라

A War for Necessities

In the border villages in Jaisalmer district, Rajasthan, death is never far from the minds of the people. 바카라We have stared death in the face,바카라 says Lal. But it is not wars between nations that he is talking about. 바카라Every day we see our elderly dying for lack of medical care, our cattle dying for lack of water and fodder바카라Šwe face death every day that we live here,바카라 he says.

Lal and others in the border villages fight a different daily battle: for potable water, electricity to run their homes and borewells, and land on which they can grow food for their families.

Myajlar receives an average of six inches of rainfall per year바카라a fifth of the 30 inches that India gets on average. The region is prone to droughts. 바카라It rains here once every two-three years,바카라 says Singh, glancing up at the clear sky, anger clouding his eyes. In between those times, the villages depend on borewells for water and to irrigate their fields. However, electricity, too, only comes to the area for 바카라about two-three hours a day,바카라 Singh adds. This makes the borewells useless for the other 19 hours. 바카라There is no timing for power cuts,바카라 says Singh. So, whenever the electricity runs바카라be it in the middle of the night or during the scorching day바카라the villagers ensure to collect enough to irrigate their fields and to provide water for themselves and their herds of cows, camels, and goats.

During dry months when the heat shimmers across the land, there is no electricity, which means there is no water. Karda바카라s villagers lose a large number of their herds, their only steady source of income. 바카라When it rains, there바카라s grass and that바카라s what the animals eat; when it doesn바카라t rain then they don바카라t eat바카라Šlike right now, many of our herd are dying for lack of water and food. There is no government fodder depot here. I wish they would open one here,바카라 says Singh.

In Karda, until 2019, there was no road to connect the village to Myajlar, the nearest developed town. An unpaved track linked the two. Sodha remembers how he went to school in his youth. 바카라I used to walk five to six hours a day to get to Myajlar from where I would catch the only bus that went to Jaisalmer,바카라 he says. A 35-km journey that both schoolchildren and adults used to make on camelback or on foot 바카라if no one had a spare camel.바카라

Now that there is a road, other problems have come into focus. Besides electricity, water in the border villages is a scarce resource. There have been improvements over the years. The 500-odd villagers used to depend on two hand-dug wells from which they could harvest nothing but hard, mineral-laden water. 바카라The water was khara, you could not even wash your hair with it. And it was totally unfit for irrigation,바카라 remembers Sodha바카라s wife Hawa Sodha.

바카라The problem is that the government바카라s improvements never get here,바카라 says 55-year-old Kamal Singh who grew up in Karda. 바카라There is an RO plant but it stands empty; a village tank that remains dry,바카라 he adds. Villagers say that most of them don바카라t have land to irrigate or farm on. 바카라The last time there was land allotment here was 50 years ago,바카라 says Singh, who shares ten bighas of land inherited from his grandfather between his five brothers. Lal, for his part, has inherited a few dozen bighas from his father, but it is scarcely enough to feed his 15 descendants. His five sons and ten grandsons, all educated to high-school level, are jobless. Some of them passed the exams for the security forces and civil service posts but were turned away at the last moment. His son spent 20 days living inside an army station in Bengal, only to be chased out when an officer demanded money. 바카라Whoever pays gets the job,바카라 Lal says.

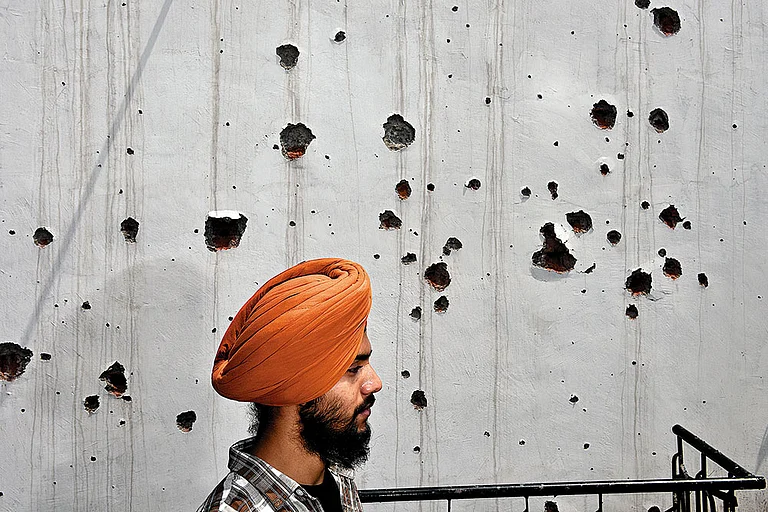

In September 2024, Jeetu Singh바카라s brother was grazing their cattle herd when he saw a glint of iron in the ground. During the monsoon, rain washes away the thin layer of dirt that covers old minefields바카라remnants of the 1965 war, when Pakistan바카라s troops occupied these villages for three months, and Indian forces mined the approaching fields to help drive them out.

That day, Singh바카라s brother exposed half a dozen anti-personnel mines near their pasture and the jungles around their fields. The villagers all know what these landmines look like because finding these is a regular routine for them. Minefields once spread six to eight kilometres inland, with the Indian army burying over 800,000 devices along Rajasthan바카라s border.

The villagers have grown up on stories of the landmines and unexploded bombs left from the war killing people. Two goat herders were blown up in the early 80s, having stepped on the wrong spot. One man was burned alive after he found a box-like explosive device and tried to open it, thinking he had found a treasure.

Should anyone get seriously ill or hurt in the border villages, there are no proper local medical facilities. Karda has one nurse in the village of 500, and they only stock basic first aid. 바카라For anything more serious, we go to the hospital in Myajlar,바카라 says Sodha. That hospital is a one-storey building housing only one doctor for the entire district. 바카라At best, the doctor can bandage you and give you a painkiller and send you off to Jaisalmer for treatment,바카라 says Singh.

So, what happens in case of a serious injury or a medical emergency? 바카라You get ready to die, what else?바카라 says Singh.

Lack of jobs and facilities in border towns has had a dual effect바카라most of the youth are leaving to find a better life elsewhere, and those who stay find themselves forced into bachelorhood. Twenty-three-year-old Viru Singh mans a medical store in Myajlar and lives with his aged parents in the village. He used to live in Jodhpur where he ran a hostel, but as his parents grew older, he gave up that life and came home. Now, he lives in a forced singlehood, he says.

바카라No one wants to marry their girls into a border village바카라why would they? Life is hard here,바카라 he says. So, two-thirds of the young men in Myajlar and the neighbouring villages are unmarried and have no hope of finding a partner to share their lives.

Those who could have found a way out. Ranu Singh ensured his daughters married outside of the villages in the city of Jaisalmer. His sons, the ones who are not sitting idle in the village, have left to find work in larger cities. Singh says young people are leaving the villages in droves. There are no jobs, not even in the army or in the BSF, which has a base just a few kilometres from Myajlar and in Tanot, the other border village.

The villagers are not the only residents of the Thar border. Alongside them live officers of the BSF바카라India바카라s first line of defence in case of war or invasion. They are also fighting another, very human, battle: one against isolation. 바카라We are in bases next to the border where we don바카라t see civilians for days at a time바카라we don바카라t see anyone for days at a time바카라Šit leads to a lot of feelings of isolation,바카라 explains Manisha Meena, a commander at the BSF base in Tanot. Twenty-four year old Meena is one of a handful of women commanders on the base.

Just 500 metres away is the wired, electrified fence that separates India from Pakistan. Commanders like Meena spend over nine hours at a time by this wire바카라patrolling it on foot, by jeep, and by camel. More often than not, they see nothing but sand. This can lead to fatigue and boredom. 바카라How long can anyone ask a person to stand and stare?바카라 says DIG Y.S. Rathore.

For the upper echelons of the BSF, the real challenge is keeping their praharies (troops) motivated and war-ready. This is achieved through a plethora of methods including instilling national pride in their work, team bonding exercises so the platoon feels like family for the officers, and visits from higher-ups, who emphasise the importance of the BSF바카라s work.

Speaking on the condition of anonymity, one BSF officer shares: 바카라To live life as a BSF officer means you will miss your other life completely바카라you go home for a few months in the year, you never see your children, you don바카라t get to speak to them about your work so they don바카라t know really what you do바카라Š it is a lonely life and an isolating one at that.바카라

바카라We Don바카라t Run바카라

Despite the difficulties바카라the heat, the thirst and hunger, the landmines and corruption바카라citizens of border towns are proud of the fact that they 바카라don바카라t run,바카라 says Kamal Singh. This land is theirs, its harshness a test of their character바카라and they take pride in that. In times of heightened tension바카라whether missiles, drones, or mere rumours fly around바카라villagers follow official directives to stay indoors. But as seen in Lal바카라s case, they long to fight alongside the force, or help in any way they can.

When peace returns, life must go on. In the fierce sun, women in bright ghagra-cholis walk barefoot to draw water; men haul fodder in trucks, hoping to feed their herds. A 1,450-km border road project announced in February 2025 is meant to improve patrolling and anti-smuggling efforts, but locals wonder if it will ever bring them a reliable electricity grid.

Behind the material problems lies a deeper yearning in the heart of these citizens: they want the border to mean more than an invisible line, a wired fence. 바카라The border towns are always willing to fight for India, but when will the government and our netas fight for us?바카라 wonders Singh.

(For full version of this article, go to www.win247.org)

Avantika Mehta is a senior associate editor based in New Delhi

This article is part of Outlook Magazine's June 11, 2025 issue, 'Living on the Edge', which explores India바카라s fragile borderlands and the human cost of conflict. It appeared in print as 'Feild's Of Nowhere.'